Ingredients In Chocolate

In this article, I will briefly go through the main ingredients in chocolate and their purpose.

1. Cocoa Beans

Flavour, Texture, & Nutrients

Dried roasted cocoa beans (left), and dark chocolate made from these cocoa beans (right). Image by Bean To Bar World.

I’m sure it does not need to be said, but there is no chocolate without the cocoa bean. This is the main ingredient in chocolate, and what makes chocolate “chocolate” be it solid chocolate bars or drinking chocolate. Keep in mind that “cocoa” and “cacao” are terms used interchangeably, and for argument sake here and when reading ingredient lists, assume they mean the same thing. You can read more about “cocoa” vs “cacao” in another article here.

Where do cocoa beans come from?

The cocoa bean is the seed of the cacao fruit, which comes from the tree Theobroma cacao. This tree grows big bright beautiful pods of fruit, and within this fruit are many large seeds. These seeds we call “cocoa beans”. To learn more about the process of chocolate making, check out these pages here.

How cocoa beans are turned into chocolate

Here I’m using a premier refiner to make some fresh bean-to-bar chocolate. Image by Bean To Bar World

Here is a very brief summary of how the beans are prepared. The fruit and the seeds are fermented together near where the cacao trees grow. After fermentation, the beans are dried (usually sun dried), and the packaged and shipped to a chocolate maker. The chocolate maker roasts the cocoa beans to develop the flavour, removes the thin paper shell or “husk”, and what you end up with is what we call “cocoa nibs”. Cocoa nibs are essentially just the kernel of the seeds (think of roasted peanuts or walnuts after any shell and then paper-like “husk” is removed. These nibs are then ground up into a paste, which releases the fat. Cocoa beans are about 50% fat (we call “cocoa butter). For a simple fine dark chocolate, the beans are ground for hours with the addition of a little sugar, and sometimes some extra cocoa butter. Once a smooth sticky molten chocolate is formed, the chocolate is tempered and shaped into bars. There is more to the story as you can read in the process of chocolate making, but this is the Cliffsnotes version.

The cocoa bean is about 50% fat (cocoa butter) and 50% cocoa solids. The cocoa solids are what contain the flavours, the nutrients (minerals, antioxidants), carbohydrates, and proteins. The fat is what gives chocolate its very unique texture. Contrary to what some believe, chocolate is not made by mixing cocoa powder and cocoa butter together with sugar. This normally would result in quite a subpar flavour and quality of chocolate. Chocolate is made today by grinding up the beans with a little sugar.

There are many varieties of cacao

There are many varieties of cacao beans. Most people in the world have only consumed chocolate made from a very narrow genetic spectrum of cacao. Fine cacao focuses on all the other varieties (which also include sub varieties, cultivars, heirlooms, etc.). Therefore, this is why most plain dark or milk commercial chocolate you had tastes more or less the same regardless of the manufacturer. The degree in flavour difference is quite minimal when compared to plain dark or milk fine chocolate.

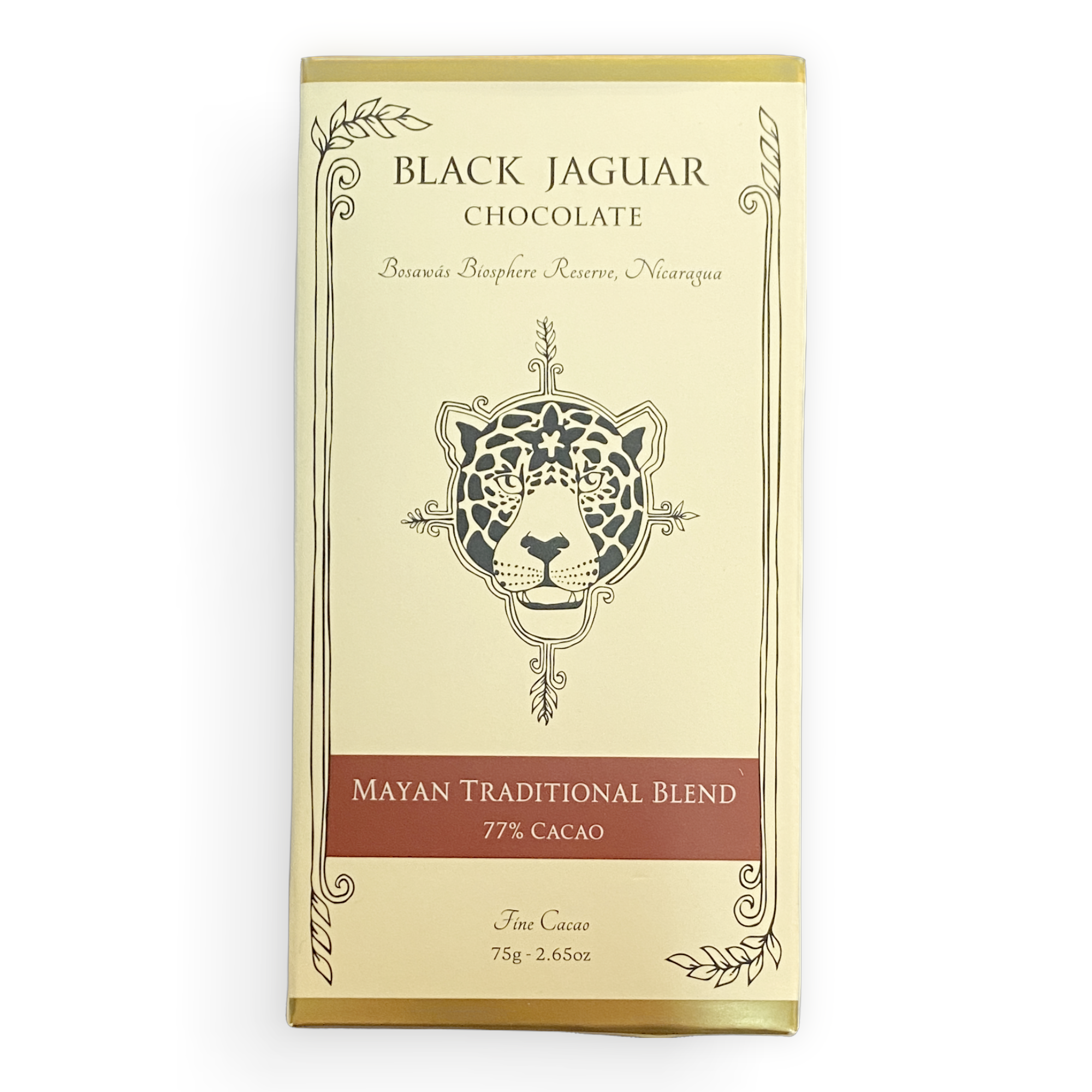

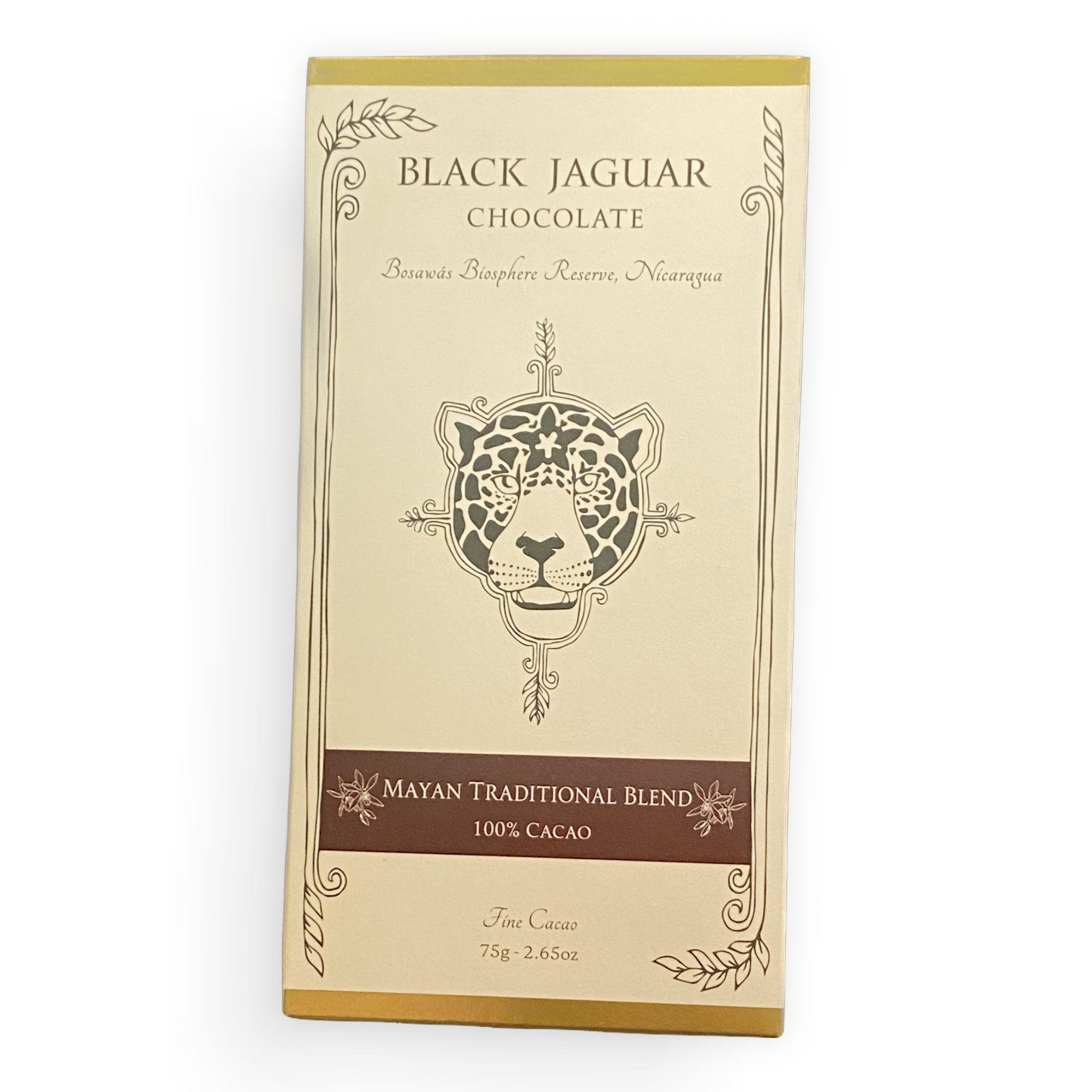

The percentage reflects the amount of cocoa bean

A 70% dark chocolate bar is about 70% cocoa bean, and 30% sugar. A 50% milk chocolate bar is 50% cocoa bean, and 50% a mixture of milk powder and sugar. If extra cocoa butter is added, it is sometimes incorporated into the % of the bar, but not always. I prefer it not be, as it can be misleading to those trying to purchase a higher percentage due to wanting a higher percentage of the nutrients. The fat is only the fat, and does not contain the minerals or flavanols. A 40% milk chocolate gianduja would be 40% cocoa bean, and 60% a mixture of milk powder, sugar, and hazelnuts (they may or may not list how much hazelnut is present). The higher the percentage, the higher the ration of cocoa bean (or cocoa nib to be exact) to other ingredients, and vice versa.

2. Sugar

Tempering Ingredient

Many people thing sugar is added to sweeten chocolate, but this is not exactly the whole truth. Sugar is used to temper the chocolate flavour. Here, the word “temper” is defined as “a way to counterbalance”, and in this case, to counterbalance the flavour. Many people think of sweet and bitter as white and black, with a grey scale in between. If something is less sweet, it must be more bitter. This is far from the truth.

Many cocoa beans do have an intense flavour, and most cocoa beans in the world are quite bitter. However, many people confuse intense flavour with bitterness, when they are actually quite different sensations. Cocoa beans are very intense. One can have a very high percentage chocolate bar of 75%, 85%, or 90% that really is not bitter at all, but may carry a heavy dark intense flavour profile.

What sugar does is it counterbalances this intensity. Yes, it can add sweetness, but there are many 70% dark chocolate bars that many would not associate with “sweet” per se, even if they are also not bitter. Sugar mutes the intensity to a level where you can begin to "taste” other flavours within the chocolate. In fine chocolate, sugar is added to a point where it can bring out the notes of spice, fruit, cream, bread, oak, herb, floral etc. These are flavours that come from the bean itself and how it was processed, not flavours added. In commercial chocolate, which is often made from very intense and often very bitter cacao, the sugar is there to reduce that intensity. However, although the intensity is reduced, there usually are no flavours that come forward beyond “cocoa”. This is usually a marker of fine vs “not so fine” chocolate.

The sugar does not just “bring out” the flavour, but the amount of sugar can really change the flavour profile. For instance, the same cholate made from the same batch of cocoa beans can have a very different flavour profile depending on how much sugar is used. A Ucayali bar at 65% will taste quite different than when turned into an 85% bar. The light fruity, nutty, and baked notes may become more sharp, heavy, and “darker” such as yogurt, cassis, woody, and toasted.

Types of sugars

The sugar added to the chocolate making process needs to be dry and often in crystalline form. Sugars such as refined, unrefined, coconut sugar, beet sugar, cane sugar, can all be used. Sugars that cannot be used include “wet” sugars such as brown sugar which is coated with molasses. Panela/Jagger can be used, but the moisture in it will have an impact on the chocolate viscosity, making it thicker. Sugars or sweeteners in liquid form cannot be used such as maple sugar, honey, or glucose. This would cause the chocolate to “gum up” and be difficult to work with, temper, and mold. However, if you were to find a source of dry maple sugar, or a dry form of a “liquid” sugar, then it usually will work.

Sugar substitutes can work as well if in a dry crystalline or powdered form. However, some powdered sweeteners such as “monk fruit powder” will thicken up the chocolate quite a bit, and cannot be substituted 1:1 for the sugar in a chocolate making recipe.

3. Cocoa Butter

Fluidity ingredient

Cocoa butter may be added into the mixture of cocoa bean and sugar. It is not necessary, but you do see this often. This is done to lower the viscosity (increase the fluidity) of the chocolate. This allows the chocolate maker to more easily and efficiently control the flow of the chocolate. It allows the chocolate to be molded more easily and without imperfections such as air bubbles. Cocoa butter is normally added in around 5-10% of the total mass of the chocolate. Cocoa butter can be costly whether purchasing some or making your own, and so is used sparingly. Also, too much cocoa butter will make the chocolate difficult to work with, and may also start to impact the flavour in a negative way.

How is cocoa butter made?

Cocoa butter was invented as a byproduct of cocoa powder manufacturing back in the 19th Century by The Dutch. Today, cocoa butter is made by pressing the beans (fermented, roasted, or not) or the cocoa nibs until the fat is released. The resulting oil is then filtered to remove the dark particles and debris from the cocoa beans and results in a fat that is yellowish when liquid, and a yellowish off-white when solid. When making chocolate, cocoa butter is usually added in the liquid form before the sugar or milk powder is added.

Lecithin

Lecithin is found in nearly all commercial chocolates and even higher-end couvertures used by chocolatiers around the world. It is a phospholipid (found in both plants and animals) which acts as a surfactant. It too also increases the fluidity (decreases viscosity) of chocolate as cocoa butter does, but to a much greater degree. It is a cheap by-product of soy oil production, and is much more cost effective to add into chocolate than is cocoa butter. However, the highest quality dark chocolate (especially eating chocolate as the bars sold here), should not really contain lecithin. It’s a contentious issue in the fine chocolate world. It does not have too bad a reputation as far as being unhealthful, but if one is allergic to soy (and most lecithin is derived from soy) this can be an issue. However, it can also come from sunflower seeds, and also be found from a non-GMO source. It is also not very “natural” in the sense that it’s not something one can just extract at home with ingredients found in your pantry.

4. Flavour Ingredients

Any ingredient other than cocoa bean and sugar is a flavour ingredient. The flavour of chocolate is based on the cocoa bean, just as coffee is based on the coffee bean and wine on the wine grapes. Once you add other ingredients such as milk, nuts, or spices, you’re flavouring it. All these ingredients can be added to the refiner (depicted above) when grinding up the cocoa nibs into chocolate, and many can also be added to the finished molten chocolate after it is made.

Milk Powder

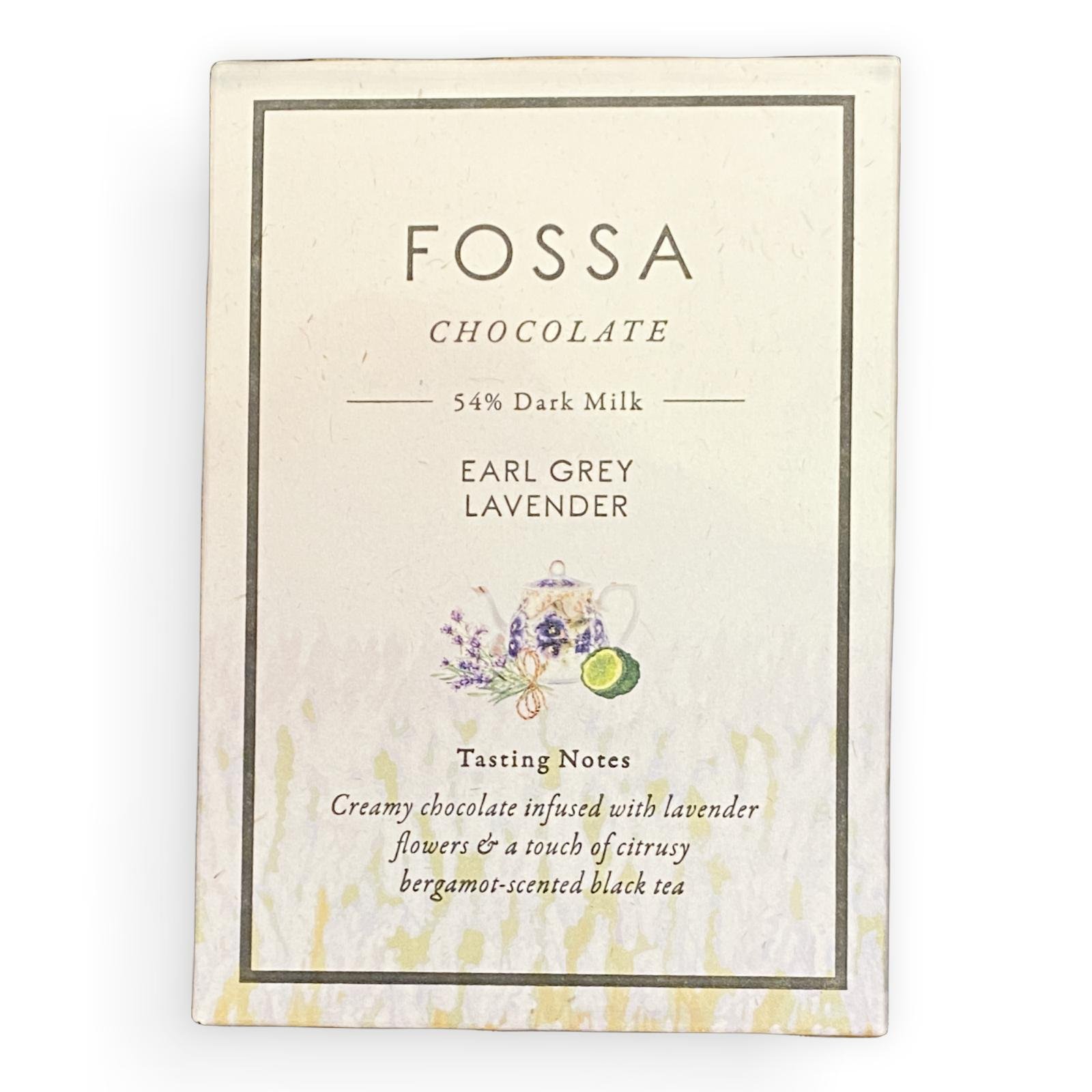

Milk chocolate was invented in the late 19th Century in Switzerland when Henri Nestle and Daniel Peters joined forces. Since chocolate is a fat-based product, one cannot really add liquid milk into the liquified cocoa beans without ruining the product (although there is a popular manufacturer in the USA that adds liquid milk to the nibs and dries them together - but most do not produce it this way). What makes milk chocolate is the addition of milk powder as a flavour ingredient, not the percentage. Many people think that milk chocolate is called this due to being very sweet, but this is not the case. Commercial milk chocolate from the grocery store is around 30-35% cocoa bean, the rest being milk powder and sugar. In the fine chocolate world, you can have a milk chocolate which is as high as 65% cocoa bean, with the rest being a mixture of milk powder and sugar. Dark chocolate should not really have any milk powder at all (or any whey or other type of dairy ingredient). If it does, this is a sign of a lower quality dark chocolate. A “dark milk chocolate” is not a dark chocolate, but simply a higher percentage milk chocolate. In this case, the milk powder is intentional, and if combined with fine cocoa bean can produce a beautifully robust milk chocolate flavour.

Types of milk powders used can include:

Dairy cow’s milk powder

Goat’s milk powder

Sheep milk powder

Any other animal milk that can be found in powder form

In the fine chocolate world, you are starting to see other dairy milk alternative milk chocolates such as

Oat milk chocolate (toasted oats)

Coconut milk chocolate (powdered coconut)

Almond milk chocolate

Rice milk chocolate

Combinations of the above ingredients

These also have to be in dry powdered form, not in liquid form, and can be added into the refiner as one would add milk powder.

nuts

Gianduja is actually a “type” of chocolate that was invented before milk chocolate in Italy in the early 19th Century. It was invented by grinding roasted hazelnuts into chocolate, but today any nut can be used. Hazelnut gianduja was a way to cut the cost of making chocolate by substituting some of the expensive cocoa bean with which was a cheaper ingredient in Italy at the time: hazelnuts. Today you can find many gianduja’s which include:

Hazelnut

Almond

Pistachio

Pine Nut

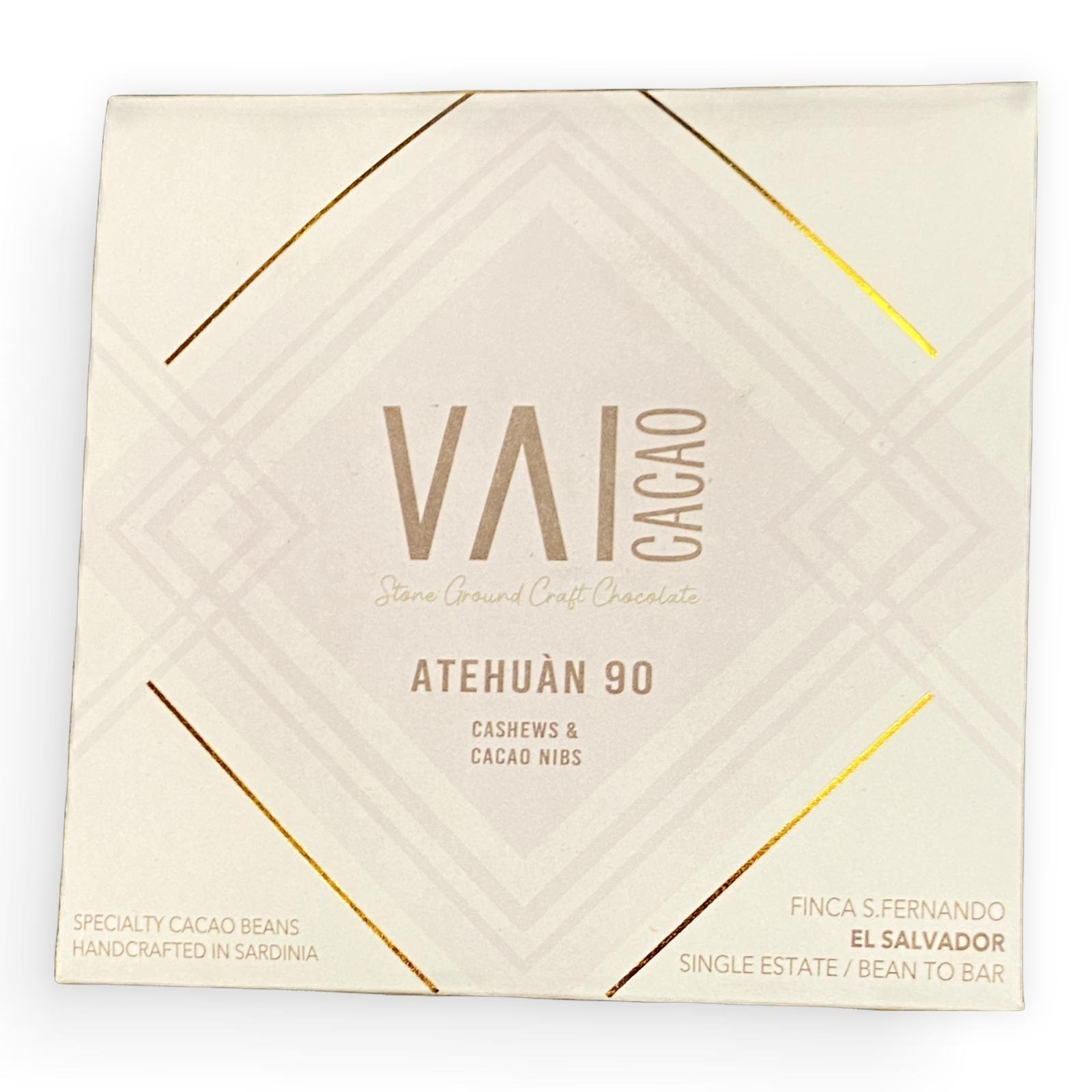

Cashew

And the list goes on.

They can also be added as inclusions in bits or whole within the molten chocolate after it is tempered, or sprinkled on bars and products before the chocolate sets.

fruits

Dried fruits can be added as ingredients in the refiner with the other ingredients either as freeze dried powders or very dry (not too wet or sticky) dried fruits. They can also be added as inclusions in bits or slices within the molten chocolate after it is tempered, or sprinkled on bars and products before the chocolate sets.

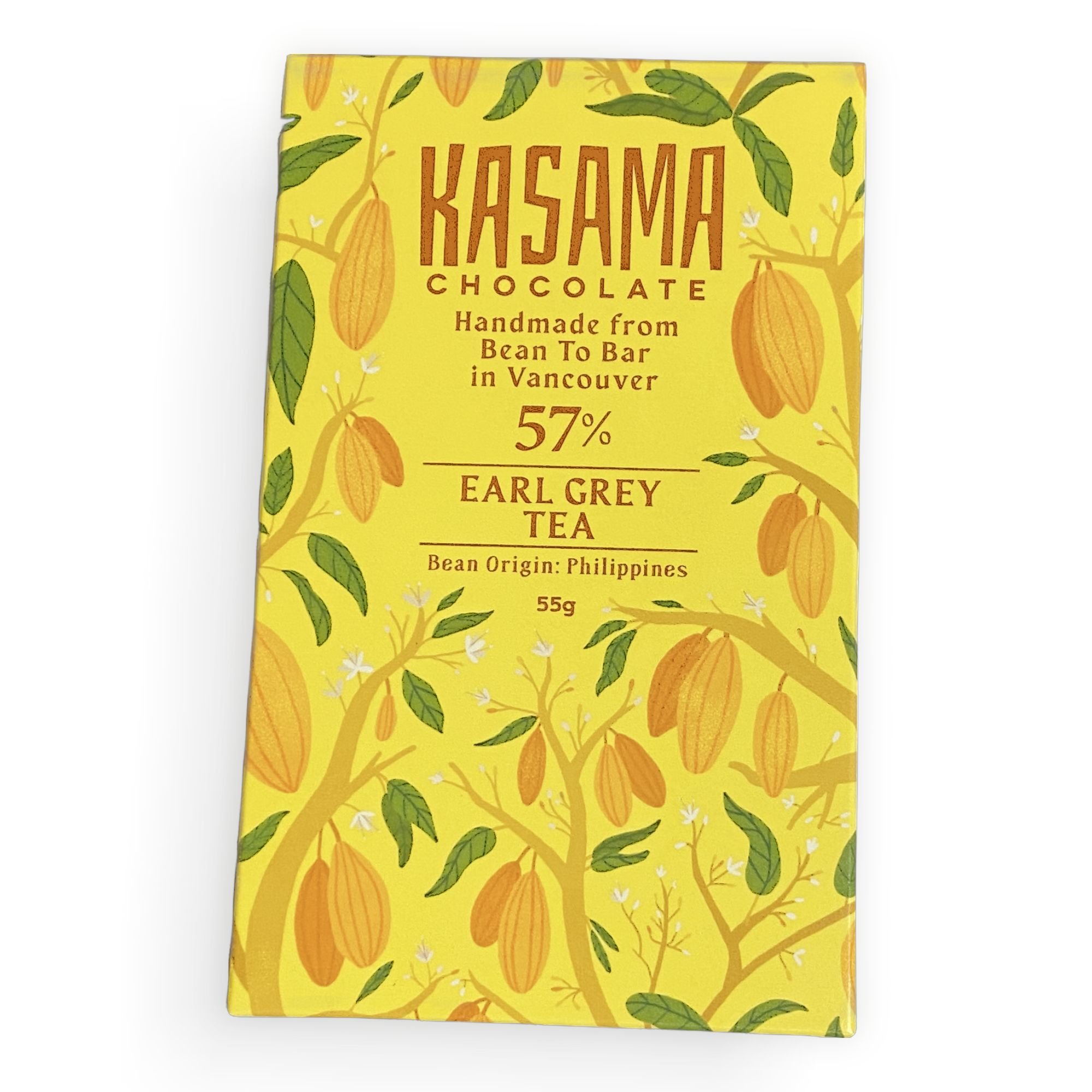

teas & Coffee

Tea leaves either flavoured or unflavoured, dried leaves or dried powders, can be included as an ingredient in the refiner as well. Ground coffee beans can also be included in the refiner for coffee bars. Below are some examples of tea and coffee being used as in ingredient in chocolate.

Just as dried fruits and nuts, they can also be added as inclusions mixed within the molten chocolate after it is tempered, or sprinkled on bars and products before the chocolate sets. Of course, chocolate covered coffee beans are also a popular confection.

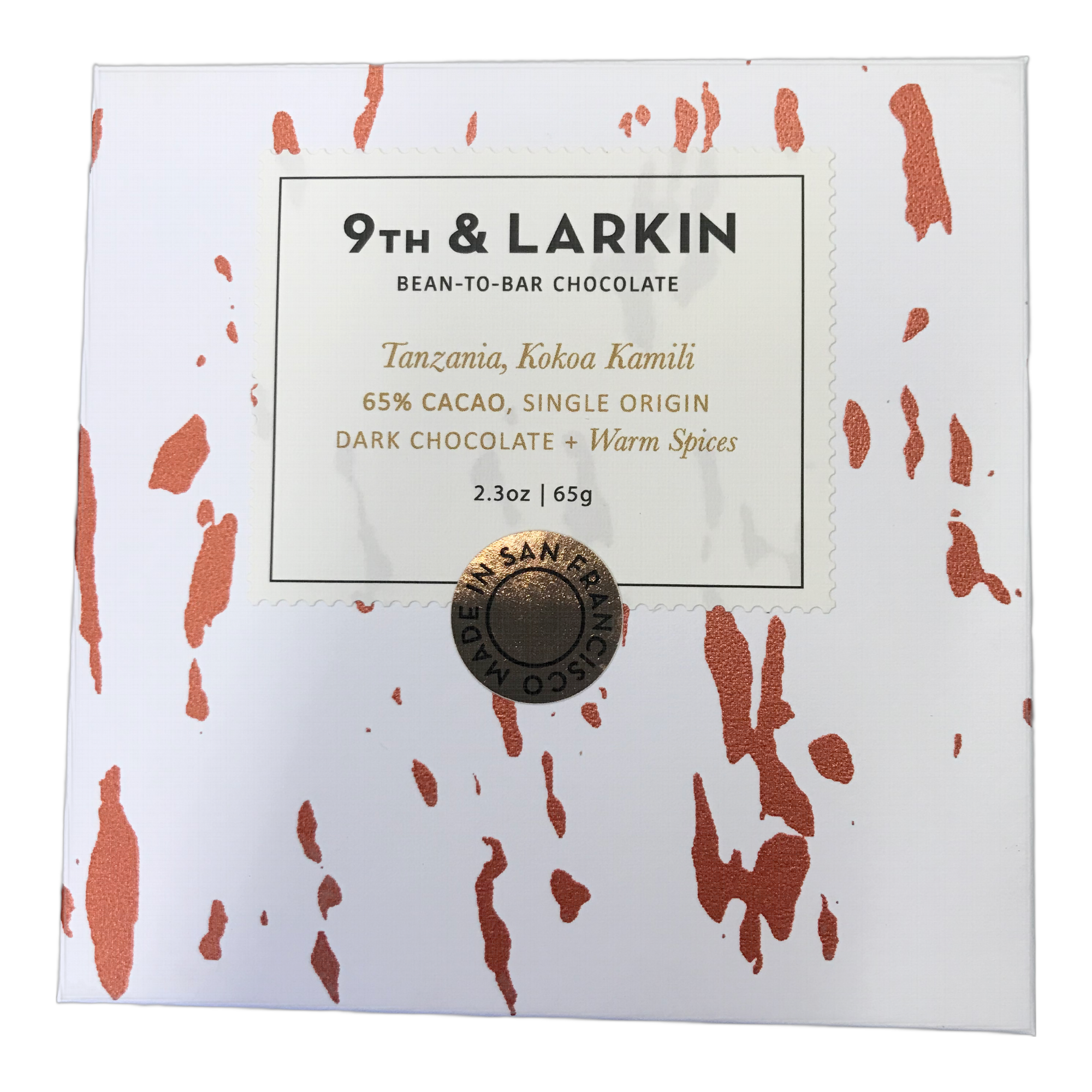

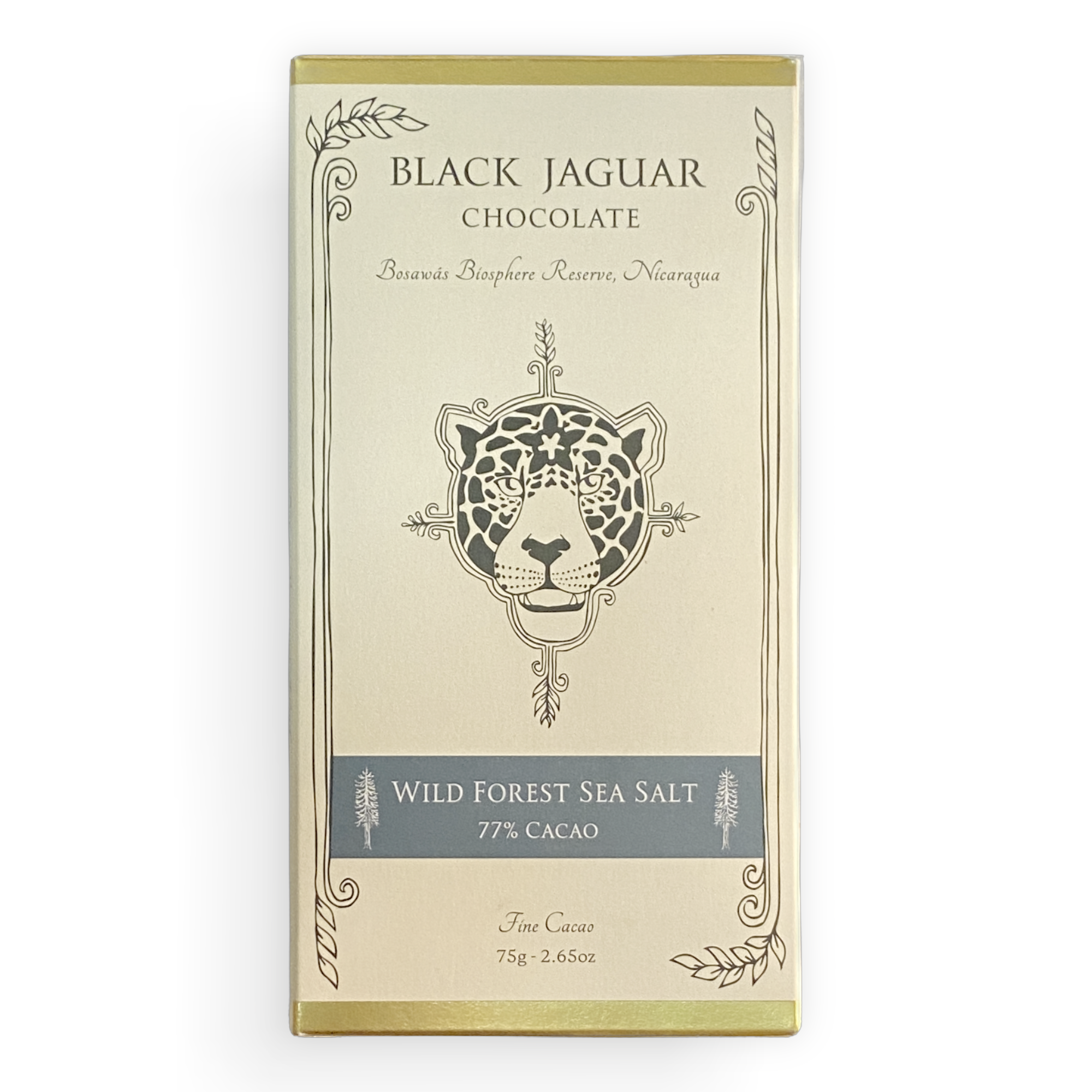

sPICES

Spices can be included in the refiner as an ingredient, or mixed into the molten chocolate before/after tempering or sprinkled on top before the chocolate sets.

Vanilla is a common spice associated with chocolate, and you find it in nearly all commercial chocolate and couverture chocolates. Why? Because most chocolates are made with a mediocre bulk commercial cocoa bean that does not have a flavour that can carry itself. Therefore, the vanilla is added to improve the flavour. Anytime plain dark chocolate bars contain vanilla, it is usually a sign that it is not of the highest quality. This is particular true of dark single-origin chocolate in the craft/bean-to-bar chocolate realm. There can be lovely bars with vanilla added for the purpose of enjoying the vainilla flavour along with the fine chocolate flavour, but fine chocolate (especially single-origin dark chocolate or single-origin milk chocolate) normally should not contain vanilla. You wouldn’t want vanilla added to your fine espresso or cherry juice added to your fine wine, would you?

Other

The types of flavour ingredients that can be added to chocolate are endless. This can also include:

Seeds

Dried Herbs

Dried Flowers

Dried Vegetables (beets, carrots, peas)

Salted Egg

Bacon

Dried Breads

Seaweed

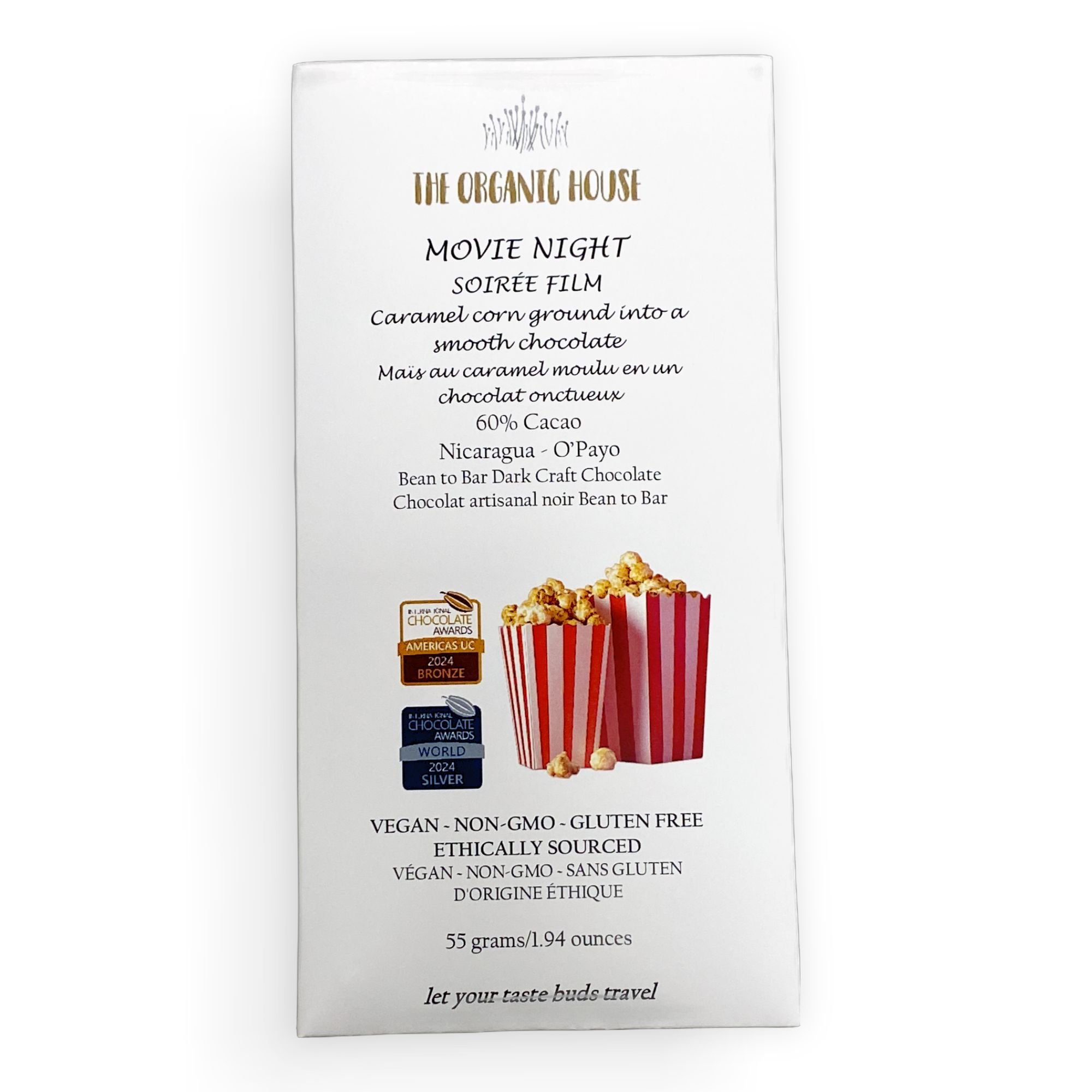

Grains And Puffed Grains

Nibs can also be infused naturally in some way before they are ground up into chocolate. This can include infusing/soaking the nibs in spirits and liquors, or even with a smoke such as the Palo Santo bar made by Qantu where the nibs were infused with smoke from the Palo Santo wood in Peru.

Ingredients to avoid In Chocolate

Lecithin

It’s hard to avoid, especially in commercial chocolate or couvertures used by chocolatiers. Lecithin in and of itself is not a harmful ingredient, and found naturally in plants and animals. It is often sourced as a by-product of soy oil production from soybeans. That said, it is not a “natural” ingredient one can create in their kitchen, bur rather something that is extracted with special equipment and ingredients in a industrial manufacturing setting. For this reason, some people try to avoid it. Some also avoid since most soy is GMO, but there are non-GMO sources of lecithin available.

It is more crucial to:

Couverture chocolate manufacturers which is required to be very fluid

Lower quality chocolates as it is a far cheaper substitute to pure cocoa butter

Milk chocolate where the chocolate becomes very thick

It is not a necessary ingredient, but an ingredient that makes the manufacturer’s life (and the chocolatiers in regards to couvertures) much easier. There is also evidence that lecithin may aid in crystal formation during tempering.

Personally, I do not want to see lecithin in any fine dark chocolate. It is not needed, and a maker who can cast and form a mold without it demonstrates great skill and attention to detail. Generally speaking, fine chocolate makers that care most about quality of the product or cocoa bean dare not dream of adding unnecessary ingredients such as lecithin. I am a bit more lenient when it comes to milk chocolate, but I still prefer not to see it in the ingredient list.

It is up to you if you are okay with lecithin in your chocolate or not.

Other fats Other Than Cocoa Butter

A high quality chocolate be it dark, milk, or white should not contain other fats other than cocoa butter. If it does, it is either a lower quality chocolate, or not chocolate at all if it contains no cocoa butter at all as is the case with “chocolate coatings”. The fat is usually a form of palm kernel oil, or synthetic CBR (cocoa butter replacers). Other than lecithin (which is based on your opinion of it) there really should be no other fats other than cocoa butter. What makes chocolate so wonderful is not simply it’s flavour, but it’s texture which comes from the fat - a unique fat unlike any other natural fat.

“natural’ and artificial flavour enhancers

A big no from me. I never want to see artificial or “natural” flavours in the ingredient list of my chocolate. Why? A quality chocolate would not contain flavour enhancers. Truth is, it is nearly impossible to avoid foods no matter how “natural” or “organic” they are without such additives. I’m not deterred by these due to any evidence that these are particularly harmful or unhealthy, but more so from a craftsman point of view. They are sort of like “cheating” to enhance the flavour of a product that really is not all it is said to be. It tricks people away from appreciating quality ingredients into appreciating end flavour, which is not the same in my opinion.

whey powder

You generally don’t want to see this, and this is often found in dark commercial chocolate. This is a sign of a lower grade dark chocolate. Dark chocolate should not contain dairy ingredients (which is not the same as a “dark milk” chocolate as mentioned above or sold in the online shop here). Whey powder is not necessary to chocolate making, and not something you wish to see in your fine dark chocolates. If you have a milk chocolate, what you want to see is milk powder specifically, not milk byproducts.

Conclusion

I hope this has helped you understand the constituents of chocolate. It can be more complex than this, but this gives you a good overview. If you wish to make your own chocolate from scratch, check out my Chocolate Making 101 page for a list of equipment and ingredients. Feel free to contact me if you have some simple questions, or check out my Chocolate Academy for free information, or book a lesson at my Chocolate School.