How do I become better at tasting fine chocolate?

Many people believe they are bad tasters. Whether that be fine chocolate, wine, coffee, or any fine food. The truth is, we can all learn to improve our “tasting” capabilities. If I were to give you a saxophone, and you never learned how to play one, I’m sure you can figure out how to use it and make noise with it. However, you likely would not be able to play it properly and make any sounds that most people enjoy listening to. For that, you would need to learn how to use it and practice, practice, practice. The same is true for fine chocolate and fine foods in general.

You may say to yourself, I practice every time I eat! The truth is, you don’t. You don’t normally analyze what the foods taste like, and try to articulate descriptive words to explain what your steak, orange, or tomato tastes like. It tastes like a steak, and orange, or a tomato. The steak may be juicy or dry, the orange may be sweet or tart, and the tomato may be flavourful or flavourless. However, we don’t normally go beyond this and really explain what that orange tastes like beyond “like a sweet or tart orange”.

When it comes to fine foods like fine chocolate, there are many tastants, aromas, and concluding flavour perceptions that we can perceive. However, we have difficult time articulating them because we just don’t practice enough with that. Think of who is always challenging themselves with reading and writing various things and building a vocabulary just through exposure and mindful reading/writing. They will have a wider vocabulary in general whether writing a formal paper or just talking with friends. The same is true with flavour. The more we train ourselves to be mindful of the flavours of the foods we eat, the wider a vocabulary we build. And not only that, but we train our brains to “taste” what’s there, just as a musician must train their ears to hear the notes they wish to play.

Some people will always be better at “tasting” fine foods, just as some people will always be better musicians than others. However, it doesn’t mean you can’t improve a tremendous deal, and learn to taste like a professional. Below I’ll go over some points that you may find helpful if you are trying to understand and improve your tasting capabilities.

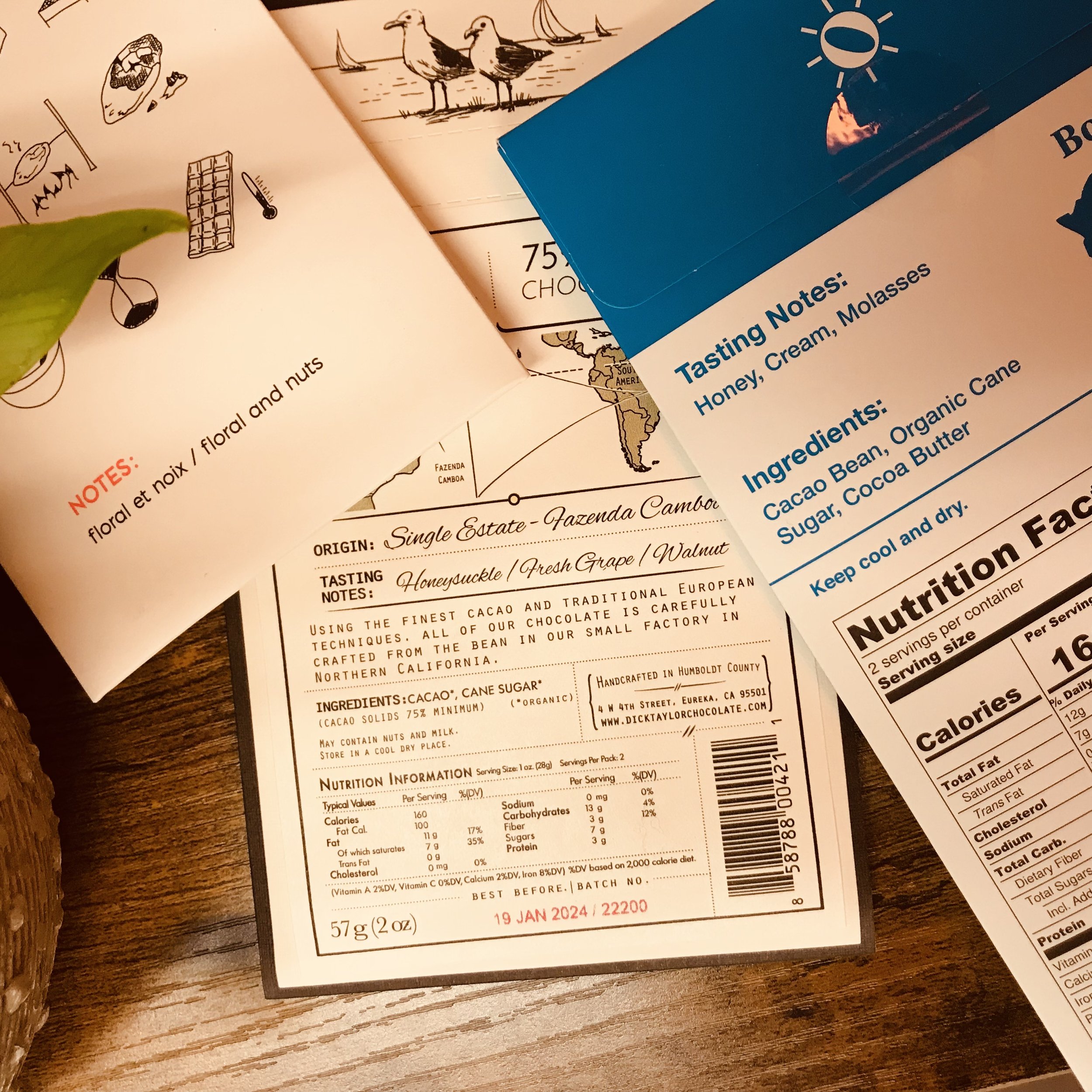

Various tasting notes or flavour suggestions as described on various fine chocolate bars. This is similar to what you may see on fine coffee, wine, tea, or even cheese.

Let’s clarify “taste”

Taste, aroma, and flavour are not the same thing, and we often conflate them. I myself still use “taste” to describe flavour, because that is how most people understand it in the English language. But let’s clarify:

Taste

Taste are the 5 basic tastes you pick up in your mouth by your taste receptors. These are bitter, sweet, salty, sour, and savory. There is research to suggest there may be more, but let’s leave it at that for now. When you eat something, your mouth isn’t picking up that it is toast or strawberry, it is only pick up those basic tastants, and of course texture.

Aroma

Aroma molecules are found in our foods in various levels. Aroma compounds are picked up by the olfactory receptors in our nasopharynx, or the space between the roof of your mouth and your nostrils. These are associated with the more specifics of our foods such as the toast, the strawberry, the nutty flavours. Also keep in mind that there are about 400 types of olfactory receptors, and many of them are turned off for you and I. As well, the receptors that are turned on for you may differ slightly from the ones turned on by me. It gets more complicated than that, but it’s fair to say that we all may have a nose with two nostrils, but the equipment inside that picks up aroma molecules may differ between us. Therefore, the way we perceive overall flavour of foods may differ. Here is a link to my growing aroma library. It includes a growing list of isolated and identified aroma compounds found in chocolate and cacao, and their associated aromas. Keep in mind that even if a compound is found in chocolate, it doesn’t mean we perceive it. And it’s not directly related to amount or concentration of that compound in the chocolate/food we eat. For instance, the compound that makes a strawberry “taste” like strawberry can be a very miniscule amount, compared to other aroma compounds in the strawberry.

Flavour

Flavour is a combination of taste and aroma, but it does not end there. Flavour is a perception or conclusion formed in our brain. In the parts of the brain in particular that deal with long term memory and emotion. This is why we have such strong emotions towards our foods, and memories of them good or bad. This is another reason why people express themselves differently in regards to what they “taste” because the flavour conclusion our brain makes takes into consideration our own background memory of foods, tastes, and smells, and draws a conclusion with the new stimuli in our mouth and previous stimuli. Not only that, but research does suggest strongly that since flavour is a perception built in the brain, our other senses such as texture, sight, and even sound can alter how we perceive the flavour of our foods!

So flavour in chocolate is a combination of the tastants we perceive in our mouth, the aroma compounds within the chocolate, but also what we see, hear, feel, and all that background memory and records of flavour/taste/aroma information stored in our brain.

What do the flavour suggestions mean?

The flavour suggestions on a chocolate bar is the way for the chocolate maker to help you, the consumer, have an idea of the flavours you may taste. Sometimes this is to help you choose a bar that you think you’ll enjoy most, and/or other times these suggestions are here to entice you with delicious descriptors consumers may gravitate towards. They normally list “tasting notes”, but as I described above, they really are not tasting notes, as they go beyond the basic sweet, sour, bitter elements of our food. However, this is just the way most people understand flavour, as it’s often described as “taste”. We don’t “flavour” our food, we “taste” it. If anyone is up for a challenge of changing the way people use “taste” and “flavour” in the English language that makes more sense, I encourage you to do so.

So these tasting notes or flavour suggestions mean that the plain dark chocolate bar you will taste has an array of flavours that go beyond just typical cocoa. If you read the ingredients of fine dark chocolate (which is equivalent to say an espresso or black coffee or tea), they include just two ingredients: cocoa beans (or their constituents like cocoa butter) and sugar. That’s it. Those suggested flavour notes are not flavours that were added. They are not ingredients they are added. They are present because they come from the bean itself and how it was cured, roasted, and ground up into chocolate. That’s what makes fine chocolate and fine cacao so profound and satisfying. Commercial chocolate is delicious for most, but very basic and predictable. Just like commercial grade fruits and vegetables. Fine cacao and chocolate made from those fine cacao beans are like freshly picked heirloom tomatoes that have a flavour you can’t describe, and in another world compared to commercial grocery store tomatoes.

Also keep in mind that yes, some of those flavours you are picking up are due to the actual aroma compounds that can be identified in the chocolate bar, but it is also that and a combination of what our own brains do with that and all the other information we are gathering as we eat the chocolate. Does the cherry flavour we perceive in our dark single-origin chocolate come from an aroma compound or group of aroma compounds actually contained in the chocolate, or is the cherry flavour a conclusion our brain makes when taking in all the stimuli from all our senses? The simple answer is a bit of both. Flavour is very complex, and not very well understood. The better you understand the science of flavour, the better you will be at understanding and appreciating fine chocolate.

Why can’t I taste the suggested flavours?

Keep in mind the suggested tasting or flavour notes are just that, suggestions. As I said above, we interpret flavour differently due to different receptors we have, different references points in our brains, and even different ambient odours and previous foods we ate that day which may alter the overall flavour of the chocolate we are enjoying. If you are enjoying multiple fine chocolates in one sitting, the order you eat them will cause your brain to interpret the flavour of the next one a bit differently, even with cleansing your palate in between. One day, an Qantu Gran Blanco bar may taste very fruity. However, another day you had it after enjoying a Qantu Morropon which is even more fruity, and by comparison the Qantu Gran Blanco all of a sudden tastes more like yogurt and espresso. Flavour is complex, and so are our results.

You may not be tasting properly. You may think that put the chocolate in your mouth and trying really really hard to pay attention to the flavours or find the suggested flavours on the label is how to taste, but you couldn’t be more wrong. There are many tips and techniques that even chocolate makers themselves don’t quite grasp or understand. You are likely not paying attention to the right things. Usually people have a hard time listening to what their body or their brains are telling them. If you ever had a good art teacher, they will tell you to draw what you see, not what you think you see. The same goes for training yourself to better appreciate fine chocolate.

How do I improve tasting?

Take a tasting class. It’s hard to find a reputable chocolate sommelier, as even those with certifications can be very unripe in regards to their level of knowledge and experience. You can always book a tasting with me, and I will be more than happy to help guide you, answer your questions, and deal with your road-blocks. You can book them as a group, or even 1-on-1 if you wish!

Use the Bean To Bar Compass. It’s more than just a tasting notebook. It’s a chocolate tasting tool and workbook. It includes all the tools you need, and ways to expand your knowledge as well. I designed this from years of research and experience, none of which one can gather from any one class or certificate class. Any class is a good place to start, but that’s jut the beginning. The work comes after the class or course. You have to put in the time to see results.

Practice, ask questions, and read, read, read. I can’t stress enough how little people actually read on the subject they wish to learn. Even in University, no one course, class, or degree will have all the information you require. Any good student knows you need to go beyond the recommended reading and the lectures, and seek out information yourself. Don’t just read the book, look at the references at the back and start reading those. Don’t just take the authors word or interpretation, go to the source. There are many pretty and fun books on bean-to-bar chocolate these days, but they just skim the surface. On my resources page you can see a list of books and recommended books if you wish to delve deeper into understanding chocolate. You will need to read on subjects that are not on chocolate per se, but will help in your understanding of fine chocolate. Also read my research summaries, which summarize primary research used by many people who write books. Also, don’t hesitate to make content suggestions for ideas and topics you can’t find answers on, or contact me directly. I’m always more than happy to help you find the answers you are looking for in regards to the craft of fine chocolate making.