How do I know which chocolate is fine chocolate?

An excellent question! Another way to say it would be, how do I determine that before I buy it? It’s a good idea to learn for yourself what constitutes fine chocolate, rather than relying on what someone else (knowledgeable or not) says about it. Learning to discern for yourself will give you the confidence you need to make better and more satisfying chocolate choices.

Steps To Determining Fine Chocolate

1. Use the Bean To Bar World App!

This is an app I developed from a map I created as the first and original bean to bar chocolate maker locator! It’s free for the business on the app, and free for you.

Locate a craft bean to bar chocolate maker in your city, state, or country. Or check out a wonderful chocolate maker in a town you may visit.

Not every maker on there is of the same caliber (some are still learning), but it’s a fabulous place to start. Therefore, the following points are still very important to be aware of.

2. Read the ingredients

I can’t stress how important this is. The first thing I look for on any bar is the ingredients list. Not so much for what I see (although that is important), but especially for what I don’t want to see.

Dark Chocolate

For dark chocolate I want to see: cocoa bean (or cocoa mass) and sugar, and that’s it.

If I see cocoa butter, that is a non issue for me. This is added to make the chocolate easier for the maker to form and to make it feel more silky in the mouth. Some purists have issue with this, but I’ll save that for another time. Cocoa butter is fat pressed from the cocoa bean, so this chocolate is still made from 2 ingredients: cacao bean and it’s constituents, and sugar.

I do not want to see:

Lecithin. Soy, sunflower, non-GMO… I don’t care. I don’t want to see it. It’s not a health concern, it’s a purist concern. Top notch incredible fine dark chocolate can be made without it, and in my opinion, the “fine chocolates” that contain it never meet the mark as far as flavour is concerned. I’m not saying the lecithin is the reason for the mediocre flavour, but when I see lecithin on the label the chocolate bar’s flavour never really meets the mark in my opinion. Think of it as a baker reaching for Crisco over butter. Butter is always better. In this case, lecithin is used as a cheaper alternative to cocoa butter to help make the chocolate less viscous.

ANY fat other than cocoa butter. Not coconut oil, no palm kernel oil, no GMO-free anything. No.

Vanilla. Again, some makers who honestly use good cacao may use vanilla. But I ask you this, would you add vanilla to your specialty espresso? Would you add vanilla to your fine whiskey? Probably not. If you really are seeking the best of the best, the cacao speaks for itself, and vanilla isn’t needed.

Natural flavour. Why? Because it is not natural. Not in the way you think. It’s a flavour additive that may or may not come from the ingredient in question. It is still synthesized in a lab. Fine chocolate is about whole foods, whole and real ingredients. If you bought a $100 or $200 bottle of wine, would you add natural cherry flavour? How about natural oak flavour? You see what I’m saying? Why is it called natural? Because it was at one point obtained from what was a living organism at some point down the processing line.

Artificial flavour. Need I say more?

To sum it up, I don’t want to see anything that isn’t cocoa bean, sugar, and cocoa butter.

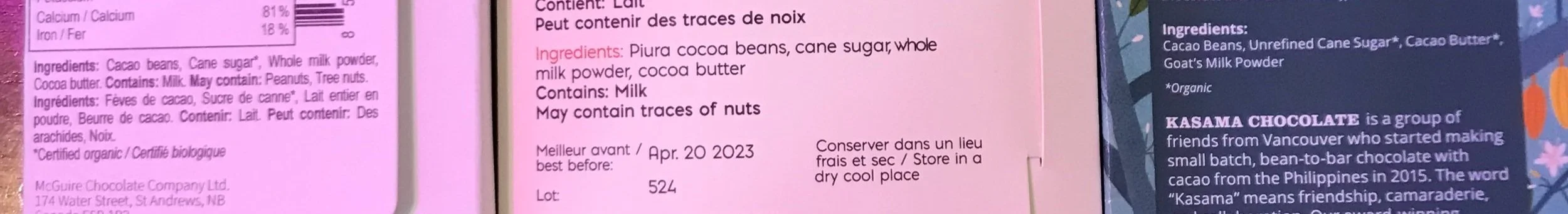

All these fine dark chocolate bars have only 2-3 ingredients. Notice how they all label the first ingredient differently (cacao, cacao beans, cocoa paste) yet they are all bean to bar makers who make their chocolate from scratch. These are all high quality fine chocolates. I don’t see anything I don’t want to see, and the ingredients are what dark chocolate should be.

Milk Chocolate

For milk chocolate I want to see: Cocoa bean (or cocoa mass), sugar, milk powder, cocoa butter.

I am (sort of) okay with, but not in love with:

Vanilla. Frankly a 10/10 milk chocolate bar wouldn’t require it. Some makers will argue it is their preference. Maybe for the cacao they have access to, they really do it. Okay, fair enough. There are some makers who use wonderful cacao, but add vanilla when making their milk chocolate. I don’t understand why, but that is their preference. If it is real vanilla, I have no issue with it. It’s not the end of the world, but I will always admire an incredible milk chocolate bar that doesn’t contain vanilla over one that does. Always.

I say this very hesitantly… I’ll whisper it actually. Lecithin. From a manufacturing perspective, the addition of sugar and milk make it very thick for the manufacturer to mold into bars. Again, fine milk chocolate doesn’t need it, but I have had incredible milk chocolate that did contain non-GMO lecithin (most lecithin used in chocolate is soy and is GMO). I know for a fact they are using high quality cacao and do not use lecithin in their dark chocolate, but they do in their milk chocolate. If you ever made bean-to-bar milk chocolate, you will understand the challenge working with it. I still prefer it wasn’t added though, just from a purist point of view.

I do not want to see:

Any fat other than cocoa butter. See above.

Natural flavour. See above.

Artificial flavour. See above.

Perfect! This is exactly what I want to see in the list of a fine milk chocolate bar wrapper. Notice how cacao is the first ingredient! Most milk chocolate you are used to have more sugar and milk than cacao. Milk chocolate doesn’t have to be too sweet. Very sweet milk chocolate is a sign of lower quality chocolate. Also notice how the bar on the far right contains goat milk powder. Craft chocolate makers are experimenting with all kinds of milk powders and even dairy-alternatives such as coconut “milk” or oat “milk”.

White Chocolate

Wait, what? A chocolate sommelier talking about white chocolate? I remember my very first interview in the chocolate world - it was a chocolate sommelier assistant. The interviewee asked me if white chocolate is chocolate. I said yes, she disagreed. I got hired anywhere, and I’m still right today. White chocolate is made not from the whole bean (as is dark or milk chocolate) but only from the fat of the cacao. It’s like an egg-white omelet. It is still an omelet is it not? Cocoa butter is a fat unlike any other in the world, and is what gives chocolate the melting and texture properties we love. Chocolate isn’t just about the flavour of the cacao, but the texture and properties of cocoa butter. Now, onto ingredients of white chocolate.

For white chocolate I want to see: Cocoa butter, Sugar, Milk Powder.

I am also fine with:

Vanilla: Cocoa butter doesn’t have a whole lot of flavour, and too much (if not deodorized) just doesn’t taste right. White chocolate isn’t quite the same as whole bean chocolate (AKA dark or milk chocolate), and so in this case, real vanilla is completely fine, and encouraged. Then when you get into flavoured white chocolates (which often are not white) then other flavour ingredients are perfectly fine. White chocolate is not like dark or even milk chocolate as it doesn’t contain the cocoa solids - which is the basis for the fine flavour notes we look for. Think of it as having a steamed milk at a coffee shop instead of a latte. A steamed milk has no coffee, so it’s just… milk. You’re not really concerned about the flavour notes of the milk, so adding flavours with it like vanilla or matcha is not an issue even for food snobs. The same with cocoa butter, you’re not looking for the fine flavour notes in cocoa butter as you are in dark or milk chocolate.

I do not want to see:

Any fat other than cocoa butter. See above.

Natural flavour. See above.

Artificial flavour. See above.

Lecithin. There’s so much cocoa butter, especially in real white chocolate, that you don’t need lecithin.

Look at the first three ingredients. Cocoa butter, sugar, and milk powder/solids. This is what real white chocolate is made of. Of course, these are flavoured with nuts and other flavourings. Still quite sweet, it is white chocolate, but a high quality white chocolate.

Ingredients don’t tell you everything

Like I said, ingredients is the first thing I read on a label. And it has more to do with what I don’t want to see than what I want to see. Why? Because lower quality bulk commercial chocolate can also be made with simple ingredients - especially nowadays when more consumers are looking for simple ingredients. The larger manufactures are creating lines of chocolate void of lecithin, natural/artificial flavours, and non-cocoa fats. Therefore, I need to look for two other important factors:

More information on the cacao

The taste (which obviously can’t be done before purchasing the bar most of the time)

3. Information on the cacao & Processing

Cacao pod grown in the Philippines. Information on where the cacao was grown and who grew it may help you determine if the chocolate is fine or not. However, country of origin isn’t everything.

The more information we have about the cacao used to make the chocolate, the more confident I am in trusting this may be a fine chocolate.

1. Origin of where it was grown

This is often why you see the term “single origin” among labels of fine chocolate (and some not so fine - even Lindt has a line of single origin chocolate trying to imitate the fine chocolate world). This is often telling you the cacao is coming from a particular origin - often country of origin such as Belize or Tanzania. However, especially nowadays, country of origin isn’t enough.

When I mention origin, I don’t only mean country origin. I mean as much information as possible about where it comes from. There should be some more information such as where in Belize or Tanzania it came from. Look for information such as what province, what region, what co-op, or even what farm. In some cases you may see “single estate” which means the cacao comes from a single farm. It doesn’t necesarily mean it is better quality because one knows the co-op or because it’s from one farm, but it may, and it also give you more information in regards to trade relationships (fair, direct, etc.)

Don’t favour one country of origin over another

Peru. Image by Fabien Moliné @fabienmoline

For one reason, it is too broad a distinction. It’s too broad in regards to whether the cacao is fine or not, and it’s somewhat too broad in regards to specific flavour expectations.

Many countries produce both fine and bulk cacao, often more bulk than fine. Although it is in a nations best interest to market their country’s cacao as the best, and have those within the fine chocolate industry stand by them (sometimes with good genuine intentions and sometimes without), country of origin these days doesn’t tell you much. Ecuador can grow some incredible fine cacao, and some terribly tasting cacao as well. The Philippines has only recently become more recognized by some fine craft chocolate makers, even though Philippines has been growing cacao since the 17th Century. It is more complex than this, but please don’t assume that because a bar is made with Venezuelan cacao it is better quality than a bar made with cacao from Samoa or Philippines.

There are some patterns in regards to flavour expectations, but they are not written in stone. For instance, often (but definitely not always) cacao from different regions of Peru tend to produce chocolate which tends to have more fruity spectrum notes (but certainly not only fruity notes). You may have seen some “cacao flavour” maps which say, for instance, cacao from Ecuador produces chocolate with floral notes. This is not quite the case. It’s much more complicated than that, and by following these expectations when purchasing a chocolate bar, you will often be quite disappointed. Ecuador cacao tends to more often produce chocolate with general notes of baked, cookie, woody, nutty, and sometimes floral.

2. The type or variety of cacao

Take this very lightly. As a consumer, the variety of the cacao isn’t as important so much as what the chocolate maker does with the cacao. Like country of origin, many will tell you only to seek out chocolate made with Criollo or Trinitario cacao. This is quite passé. Trinitario is not a variety (it’s a hybrid), and there are many more varieties than have been suggested. The truth of the matter is though, variety doesn’t hold too much weight either, since there is a great amount of variation between different populations of the same variety of cacao (and many which are mixed breed varieties).

A bar can be made with what is stated as criollo cacao, and taste mediocre and uninteresting, while cacao made with chocolate that has a “mutt” of genetics including amelonado can still produce some incredible tasting cacao. Cacao genetics is very complex, and most have a hard time understanding it. Even within these varieties are sub-varieties, strains, or even individual trees that produce seeds with very different characteristics from other trees of the same variety.

As a consumer, you’re not buying the cacao, you’re buying the chocolate. It’s what the maker does with the cacao (roast, refine) which determines the final flavour of the chocolate, not the variety. Although it helps a little to know as much as you can about the cacao (and I encourage makers to do to same on their packaging) it doesn’t mean much to you as a consumer in regards to quality or flavour. It’s important to know that the maker knows as much about the cacao as possible, and that may help you to trust the brand and quality of the chocolate, but I never look for a specific variety. Genetics and variety is part of the flavour development story, but fermentation, drying, roasting, refining, conching (if applicable) all have a massive impact on the final flavour of the chocolate.

For me, more information from where it was grown and who grew it is more important. Why? Bulk commercial cacao is not easily tracible. When a maker knows not only the country, but where in the country, who farmed it, the variety, then I can feel more assured it may be a high quality chocolate.

3. Mention of making it from bean to bar

Qantu Chocolate based in Montreal shows the process of chocolate making right on the front of the bar wrapper. This doesn’t mean the bar is made by a bean-to-bar maker, but this information as well as the other mentioned does help. Turn the bar around and read what the brand/maker has to say about their product! When in doubt, visit the website.

I really encourage high quality bean-to-bar makers to write somewhere on the bar that they roast and refine their own cacao. Hey, if you grow it and/or ferment it too, put that on the bar! As a consumer, it’s important to know that the chocolate maker had full control over the flavour development of the cacao and chocolate, at least from the raw cacao stage. If the maker lives where cacao is grown, they may even be able to have a hand in fermentation or even grow the cacao themselves! We are seeing more of these. Again, this doesn’t guarantee the chocolate is incredible, but it helps in making my decision.

Some will write “bean to bar” somewhere on there, and that they make it from scratch, from the bean. Some brands like Qantu even have little pictures of the steps of making bean to bar chocolate on the front of the wrapper.

However, we are beginning to see “bean to bar” on products that don’t represent chocolate made by an actual bean-to-bar chocolate maker. Read more hear about what it means to be a bean to bar chocolate maker or the term “bean to bar”. Bean-to-bar means that the maker took the raw dried cocoa beans, roasted, winnowed, and refined it themselves into chocolate. The roasting and refining have a huge impact on the flavour, more than most people know. There are many private labels who don’t actually make the chocolate themselves, but have another (often commercial chocolate maker) produce it for them. That’s one way to start a chocolate company, and nothing is wrong about that per se. However, the fine chocolate world is not only about flavour and quality, but about quality craftsmanship and showcasing the men and women who have the skills to create beautiful incredible chocolate.

Therefore, be sure to look not only for bean to bar, but also mention that they make the chocolate and how they make it. There are many times you won’t see this, and that does not mean it isn’t really bean to bar either. Something to be aware of.

4. Taste it!

I know I know. You can’t always ask for a sample, and sometimes you are buying the chocolate online. However, no matter how through I am with reading ingredients (what should be there and what shouldn’t) information on the cacao, on the process, it still comes down to taste.

Keep in mind that not all makers who call themselves fine or craft chocolate makers are fine. Some are still learning, some are not using great cacao, and some frankly just don’t know what they are doing.

But alas, you bought your, what you believe to be fine chocolate. Now it’s time for the taste taste. But what to look for? Below I will give you some quick tips. If you want to learn more on your own, consider purchasing my Bean To Bar Compass to help develop your tasting skills, book a fun educational virtual tasting with you and your friends, or book a 1-on-1 virtual tutoring lesson. Here are some quick pointers.

Low to no bitterness

Many assume dark chocolate should be bitter. It should not. Bitterness is most often a sign of poorer quality bulk cacao. Some fine chocolate bars which are 70% taste like a 50% commercial bar. The difference can be that drastic.

Now, many who are used to milk chocolate, very sweet foods, will have a high threshold for sweetness. Therefore, what I would call not bitter, they would say is bitter. What I would call intense, they would call bitter. When I say bitter, think of that bitterness in grapefruit, dark IPA beer, or bitter melon. That bitterness. A good quality chocolate of 70, 80, or higher percent shouldn’t have that bitterness.

Now there may be some bitter aftertastes in some bars made by some very reputable fine chocolate makers. That’s to be expected. Cacao isn’t either bitter or not bitter, there is a range. Perhaps they chose that cacao because they really enjoy the flavour profile and are willing to put up with a hint of bitterness.

However, good quality roasted cacao and dark chocolate should have little to no bitterness.

Fun Fact Salt can actually act as an inhibitor for some bitter receptors, and reduce the perceived bitterness of some chocolate.

Low Acidity

The acidity is built up during the fermentation, and some cacao is more acidic than others. It is up to the maker to control for acidity when they roast and refine their cacao into chocolate. Now, a little tartness is not a sign of poor quality. In fact, a little tartness may help enhance flavour just like a little bit of sugar does (or even salt).

Now, if it is puckering sour. If you can feel the sourness in your throat as if you ate a lemon or drank some vinegar - that in my opinion is not a high quality chocolate. Perhaps it could have been! It could be a great quality cacao that wasn’t processed well enough. Granted, there are makers who choose to under roast their cacao, which increases the acidity of the chocolate. However, there should be a limit, and I’m sorry to say that this chocolate is not a high quality chocolate.

Too much sugar masks the flavour, too much bitterness hides the fine aromas, and too much acidity does so as well. It makes it difficult for the consumer to enjoy the beautiful underlying aromas in the fine chocolate. There is some award winning chocolate out that that does feel like I just drank some vinegar. This ties into another point coming up on why you shouldn’t take awards on bars too seriously.

Complex, interesting, wide ranging flavour

There are two main reasons why some people who never tried fine chocolate don’t like it the first time they try it:

It doesn’t taste the way they expect chocolate to taste

We all grew up with dark, milk, and white chocolate. We have expectations of what they should taste like. The commercial chocolate out there all, to a degree, taste the same. Our dark chocolate bar is expected to taste like cocoa. When it comes to fine chocolate, many will taste like chocolate and then some. A high quality dark chocolate will contain a wide variety or range of notes that may include: berry, pear, hazelnut, woody, herb, mint, floral, baked, cookie, caramel, spice, bread… and the list goes on. These are not ingredients or flavours added, these are flavours your brain picks up due to the type of cacao, how it was processed, and your individual judgements of the flavour.

Some people love the fact that some fine chocolate tastes so different, and some don’t taste like chocolate at all. Some enjoy what they grew up eating. For myself, I never cared for dark cholate growing up, or chocolate in general. It was only when I was properly introduced to fine chocolate that I began to enjoy chocolate the way I do today. Perhaps the same would be for you.

They were not shown what to “taste for” and how to appreciate the flavour.

I can’t count how many people I have taught or conducted a tasting with that experience fine chocolate in a whole new way, just by a few tips and knowing what to look for. The same person can taste fine chocolate and completely miss what is literally right under their nose!

There are many chocolate “sommeliers” out there, but many don’t know how to train or explain how to actually get the flavour from the chocolate. And for some, they really need to understand how to do that. So perhaps you tried fine chocolate before, but didn’t think it tasted like anything special. Perhaps it wasn’t special, or perhaps it was and you just were not instructed well. It may be worth to give fine chocolate a couple more tries before you establish what you think of it. Book a tasting with me, or check out the Bean To Bar Compass (below).

No off flavours

Not flavour, flavours (which are actually tastes)

You don’t want to taste: too much bitterness, too much acidity, or too much sweetness. I don’t want these in my fine chocolate.

Off flavours

Tasting these may be a sign of poor quality: very burnt, metallic, medicinal (think your ibuprofen pill), hammy, mold, barn (you know, the way a barn smells - I hope you don’t know the flavour of a barn)

There will be some flavours your brain doesn’t agree with. There may be preferences you don’t like, but these are not off-flavours in the sense that they don’t deem the chocolate lower quality.

Want to learn more about fine chocolate flavour and improve your tasting capabilities?

Check out my Bean To Bar Compass, a tool and workbook I designed to help beginners and intermediates improve your tasting skills and better understand the flavour of fine chocolate.

other markers Of potential Quality

I won’t go into too much detail here, but these are factors that for me don’t help me decide whether a chocolate is fine high quality chocolate or not. Many of these can be and often are associated with fine chocolate, don’t get me wrong, but they in and of itself don’t honestly tell you much about the quality of the actual chocolate.

Percentage

Percentage has nothing to do with quality of the chocolate. A really incredible dark chocolate can be 65, 75, or 85%. The percentage on a bar is supposed to reflect the amount of cacao bean versus the other ingredients. A dark chocolate made with cacao and cane sugar that is labelled as 70% will contain 30% cane sugar. A milk chocolate which is labelled as 50% will contain 50% cacao bean and 50% a mixture of milk powder, sugar, and cocoa butter.

Organic

Is not synonymous with quality. There is organic fine cacao as an ingredient, and there is organic bulk cacao as an ingredient. There is organic certified fine chocolate, and there is organic certified bulk chocolate.

Is organic good? In the true sense of the word, yes, but it is not synonymous with quality of the cacao and therefore quality of the chocolate.

Fair Trade

Similar to organic. There is fair trade certified chocolate made with low quality bulk cacao, often sold at around $5-7 CAD a bar. There is also fine chocolate made with fairly traded cacao which is not certified. The bean-to-bar makers out there are often seeking fairly traded cacao on top of a high quality cacao, they want both. The problem is the red tape and cost for both the makers and the farmers to establish this certification. Many small-scale manufacturers can’t afford this, or won’t as it they know they are better off paying the distributor, co-op, or farmers directly to ensure more of the money goes to where it is supposed to. Something to seriously consider next time you shop only looking for those certifications.

If you find a brand of fine chocolate you like, learn about it. Look at their website if the bar doesn’t say and see where they are getting their cacao, or email them and ask them.

Awards

Awards are fun. Awards are great for the makers to give them more marketing credibility. Awards are also handed out like candy. Everyone has them. Well, nearly everyone. Sometimes the awards are for best wrapper! Who cares? I want to know which is the best chocolate. Most awards revolve around chocolate being judged by people who have little to no knowledge of fine chocolate. Most judging panels don’t conduct a blind tasting. What does that mean? They know who the maker is, and much bias comes into play here.

Are awards bad? No. Award ceremonies are a great way for makers to network, for them to showcase their products. However, don’t assume that an award means you’ll love the chocolate. Also don’t assume it means the chocolate must be high quality. One example I’ll give you is a maker from the USA. First bars I tried tasted moldy. I gave them another shot, same thing. Another shot again - different batch, different bar, same thing. And this is an award winning bean-to-bar chocolate maker. Their packaging? Spectacular. Their branding - top notch. Their personality - Mr. Congeniality! Their chocolate - not worth the calories in my opinion (and many others in the industry secretly agree behind the curtain). I later found out that they don’t maintain their dried cacao well, and although mold can grow on dried cacao to some degree, the degree there seems to be in need of a bit more attention.

Don’t feel bad if you taste an award winning chocolate and you hate it. It could be your preference, or it could actually be a terrible chocolate.

Country of manufacturing origin

Is it Belgian? Is it Swiss? Is it French? It must be good! No, it really must not be. Don’t get me wrong - there are some fine chocolate makers in these countries, but don’t assume country of origin equates quality. In my opinion, when it comes to more commercially available chocolate - the French do a much better job than the Belgians. The Swiss do a much better job than the Germans, but all of them pale with a high quality bean-to-bar maker from Canada, USA, Peru, Brazil, South Korea, and the list goes on.

Today, the best chocolate in the world is made anywhere you have a very skillful maker who gets their hands on high quality cacao. The combination is unstoppable!

B certification

Ditto to # 1 and #2. I wouldn’t even blink at it. Good cause? Does it really do what it claims? Maybe - to some degree. Maybe there are better ways.

Vegan

Absolutely not. In fact, high quality dark chocolate should ALWAYS be vegan, or at least 100% plant based. Only very low quality dark chocolates contain whey or milk or anything else to make it not vegan friendly. I same 100% plant based because some fine chocolate is made with refined sugar, and some vegans have issue with this. Although, for the most part, fine chocolate makers tend to use unrefined cacao.

sustainable

There’s nothing more sustainable than supporting the relationships of small-scale entrepreneurs who make incredible chocolate and do so by supporting farmers who grow this incredibly challenging crop. Just saying sustainable isn’t enough, and bulk cacao of poor quality can be labelled as sustainable as well.

Summary

Read the ingredients

Simple. Less is more.

Key ingredients you don’t want to see

Look for as much information on

the cacao (variety, Where it was grown, who grew it)

the process of bean to bar (roasting, winnowing, refining)

Taste it!

The most important. No matter what, it will come down to taste.

Even if the cacao is high quality, and the maker is bean to bar, you will have to taste to see if they have the skills to produce fine chocolate.

Taste it mindfully, by paying attention to the specifics mentioned above

Don’t be mislead by impressive labelling

Be aware of the jargon surrounding specific labelling on chocolate:

including but not limited to fair trade, organic, awards, origin, and other certifications or logos. Be sure they are transparent about what they stand for. If you are unsure, it’s up to you as a conscious consumer to thoroughly look them up and see for yourself.

Lean about your maker.

Check their website, see if what they do and what they support is in line with what you value.