A Chocolate History

If you really want to master chocolate, you need to begin by learning its history. Having an informed yet objective view of the history is the only way to truly appreciate it, whether eating it, making it, or using it in the kitchen. The following is a brief overview. Take your time, and perhaps read it while you’re enjoying your favourite dark chocolate while thinking about how it relates to what you’re reading.

Click a heading to read more.

Timeline

15 000 to 10 000 years BC

Theobroma cacao evolves; humans first inhabit South America

3 500 to 3 300 BC

Earliest evidence of cacao consumed as a drink (discovered in Ecuador)

+ Part 1: A Fruity Beginning

When we think about chocolate, fruity is not usually a flavour that comes to mind. However, it's the fruit of the tree, Theobroma cacao, that first attracted humans to this plant. Chocolate is made from the seed of cacao, each segment surrounded by a fleshy sweet and tart fruit.

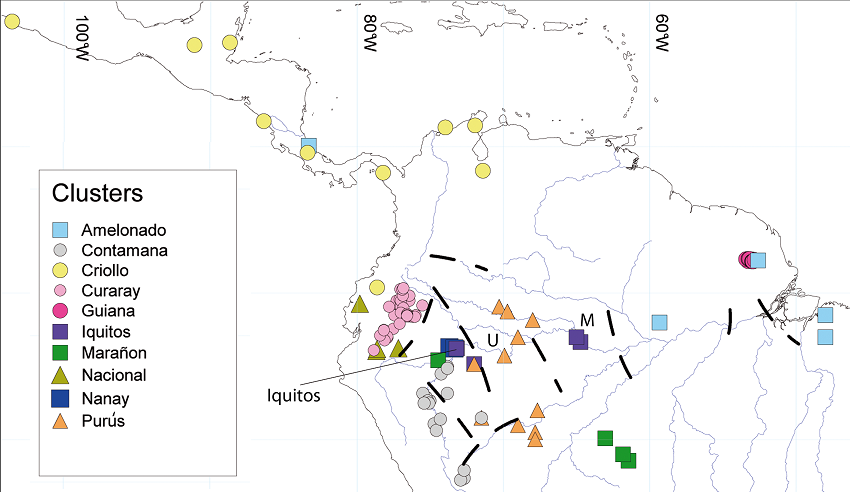

The genus "Theobroma" is native to the hot and humid Northern Amazon region of South America. Humans are believed to have entered South America around 15 000 to 10 000 years BC, which coincidentally is around the same time the species Theobroma cacao is believed to have come to be in the Northern Amazon. For this reason, it has been hypothesized that humans may have crossed different species of Theobroma and unintentionally created the species T. cacao.

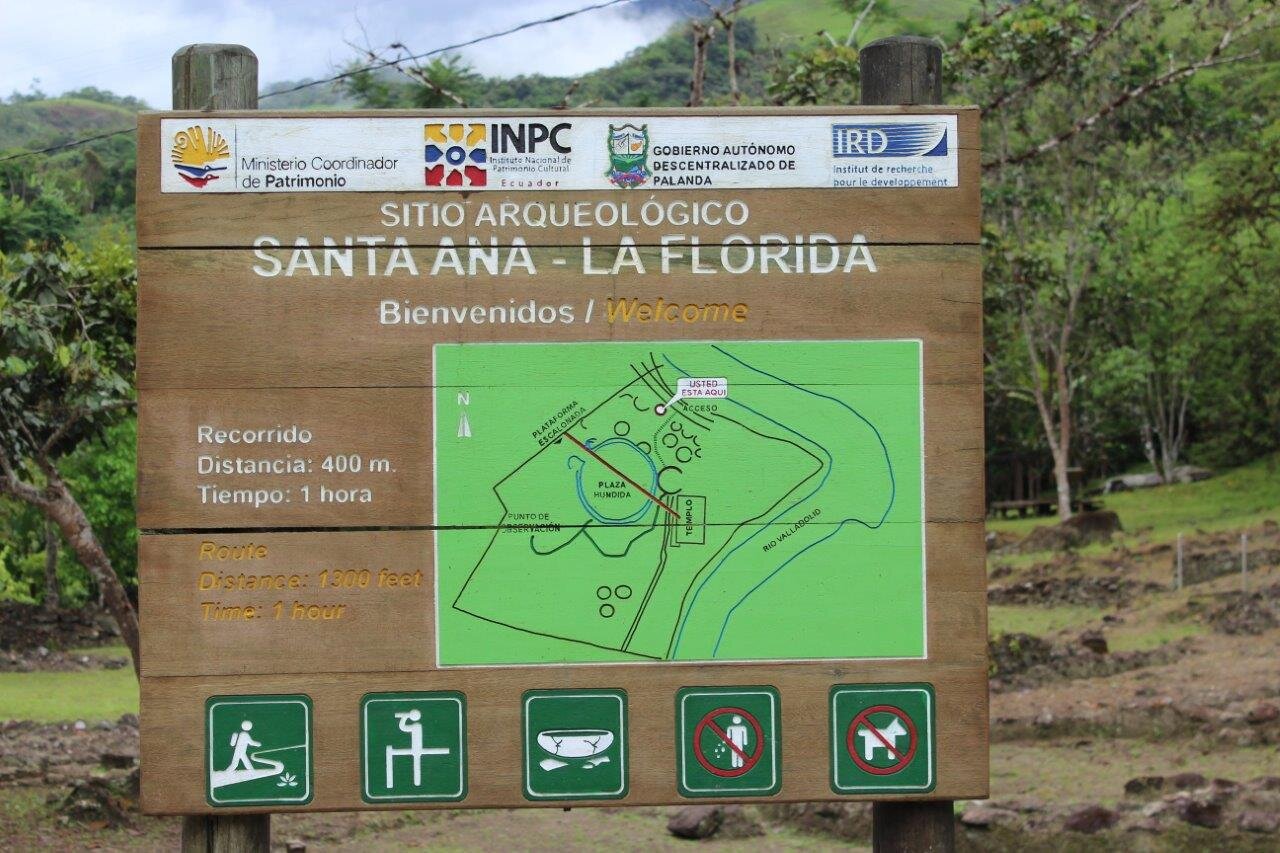

From The Northern Amazon, cacao was then transported North into what is now Southern Mexico and Guatemala, via migrating humans and possibly through trade, and planted in regions along the way. At some point in history, the seed of the cacao became utilized to create a drink. Today we call that drink chocolate, but we don't know what the original name for it was. The earliest evidence we have of chocolate exists at the site of Santa Ana-La Florida in Southern Ecuador. Pottery meant to hold liquids were found to contain the chemicals theobroma and caffeine, dated to as early as 3500 BCE. These two alkaloids are found only in cacao seeds and not in any other botanicals in this region of the world.

As cacao migrated Northwards into the Isthmus of Panama to Southern Mexico, a variety of cacao was established, known as Circum-Caribbean or "Criollo" cacao, which was different from the varieties from which it originated. This cacao will later be coveted for its delicate aroma and dynamic flavour.

The exact path of cacao into Mesoamerica, where chocolate culture flourished, is not known. There has been a suggestion that the Circum-Caribbean cacao already existed in Central America before humans arrived. The other theories suggest it was taken one of two routes. One begins in Northern Amazon, and goes North East, across the Guianas and Venezuela, into the Northeast corner of Columbia (carried there by humans over the arid Caribbean region), then into the wet region of the Gulf of Uraba, and into Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and its most Northern region of Southern Mexico. The second suggestion is that humans carried cacao West from the lower Eastern Andes (Colombia and Ecuador), going West and crossing the low mountain areas moving toward coastal Ecuador and Columbia, then into Panama and eventually Southern Mexico. Since we now have evidence of chocolate being made in Ecuador as early as 3500 BC, the Western route seems more likely.

Whichever way cacao traveled, these early humans adored this little seed so much that they went through the effort of migrating with their babies in one arm and the seedlings of T. cacao in the other.

Many species of Theobroma grow large pods of fruit as well, so the question remains, why did humans chose T. cacao specifically to bring with them on their migration routes? There were many other Theobroma species and South American fruits surrounding them. However, we are grateful they did, as it lead to the creation of chocolate.

Timeline

3 500 to 3 300 BC

Mayo-Chinchipe drink cacao

1 800 BC

Mokaya consume chocolate

1 500 to 400 BC

Olmecs reign in Mesoamerica

1 000 BC

"Kakawa" enters Olmec vocabulary

+ Part 2: Chocolate Culture Develops

Although native to the Amazon region, cacao likely wasn't widely domesticated by humans until it reached Mesoamerica. However, recent studies highlight evidence of chocolate making found in pottery from Santa Ana-La Florida in Ecuador dated 3500 to 3300 BC. The pottery that contained cacao was likely a vessel for liquid, and so chocolate could have been prepared as early as 3500 BC by the Mayo-Chinchipe. Next, we have evidence of cacao consumption from pottery of the Mokaya people of Soconusco in Mexico dated as early as 1800 BC.

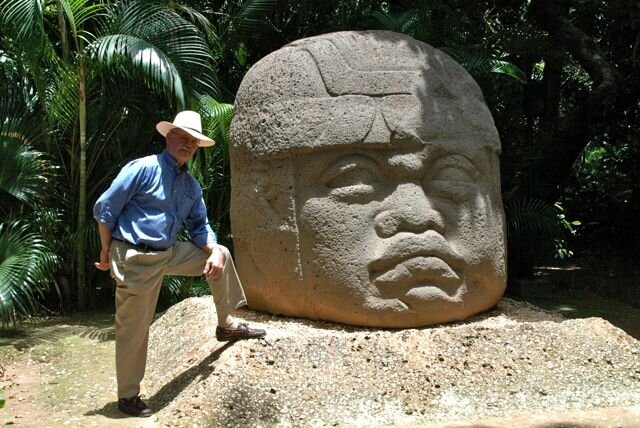

Olmec society appeared in the Mexican Gulf Coast around 1500 BC to 300 BC. They created the first Mesoamerican city at the site of San Lorenzo, with evidence of chocolate making in pottery and language. Their word for chocolate, kakawa, has been a vocabulary item in Mixe-Zoquean (a language likely spoken by the Olmecs) by 1000 BC, the peak of Olmec society. It is speculated that it was they who were the first to domesticate corn, and invent nixtamalization, both being pivotal in fueling North American civilization, leading to the proceeding empires.

How chocolate came about is still not fully understood. However, by understanding Pre-Conquest American culture, history, and the methods for which they made chocolate, we can speculate how chocolate may have been invented.

The pulp contained in cacao pods was fermented to create alcoholic drinks. It's this fermentation process of the pulp and seed mass that we now understand to be crucial in developing the flavour of chocolate within the seed. Then, at some point in history, humans began roasting these post-fermented and subsequently dried seeds. Roasting allows the flavour of chocolate to fully develop in the seed. It’s not known if these “chocolate flavoured” seeds were consumed as is before incorporating them into a drink, or made specifically for the chocolate drink. However, eventually they were ground into a paste, and combined with water to create kakawa, a chocolate drink. These drinks also contained other local ingredients such as chilli, antioche, vanilla, and maize, and the versions of this chocolate drink were endless. This mixture is what chocolate was for most of its history.

For thousands of years, this invention of chocolate became a Mesoamerican cultural icon, fueled trade and commerce, triggered warfare, and became a symbol in their spiritual beliefs.

Timeline

2 000 BC

Maya culture begins

1 500 to 1 200 BC

Izapan culture begins

300 BC

Olmec empire falls

400 BC to 100 AD

"Kakawa" enters Mayan vocabulary

+ Part 3: The Future of Chocolate

The Olmecs were gaining control and extending their trade routes on the Mexican Gulf Coast, spreading their culture, including chocolate. Meanwhile, The Maya show up in Yucatan and Guatemala as primitive farmers by 2000 BC, while Izapan culture was growing in South Eastern Chiapas as early as 1500 to 1200 BC. As the Olmec culture and trade grew, it began to show up in Izapa, as seen in their pottery, between 1200 to 300 BC. However, the leading Olmec cultural centre, La Venta, began to fade by 300 BC, around the time Izapa grew into a major Mesoamerican centre of culture.

Izapan culture is important to the story of chocolate because, although the Maya, Olmec, and Izapans all existed at the same time, evidence shows the process of chocolate making appears to be handed down from Olmec to Izapan culture, and then from the Izapan to the Maya. The Maya would become the next great empire after the Olmecs in Mesoamerica.

The Olmecs are believed to have spoken Mixe-Zoquean, which is also what the Izapans spoke. The word “kakawa” (meaning “cacao”), a Mixe-Zoquean word, appears to have entered the Mayan language after Olmec culture already began to fade, and while Izapa was at its peak, between 400 BC and 100 AD. This offers the idea that the word for chocolate, and chocolate itself, was likely passed onto the Maya by the Izapans, not directly by the Olmec.

The Popol Vuh was the Mesoamerican divine word, for which cacao appears many times. Its narratives date as far back as the Izapans, and continued into Maya culture. The Izapans appear to have also influenced Maya culture with the invention of the stela and altar cult, as well as a greater importance on centralized power by chiefs and religious figures. Aspects of Maya art are found in their earlier forms in Izapa. As well, Pre-Classic Maya sites have turned up Stelae that resemble those of Izapa.

Since the invention of chocolate, dominions would rise and fall, along with aspects of their culture. However, cacao and the process of chocolate making was important enough that it was received, preserved, and even heightened in importance in each proceeding culture.

As Izapa became less influential, the Mayan culture grew in Northern Guatemala and Southern Yucatan beginning to expand their empire. The only written evidence referring to cacao can be found on vessels in tombs and graves of the Maya elite.

The Maya

Timeline

2 000 BC

Preclassic Maya exist

250 AD

Classic Maya era

800 AD

Classic Maya collapse

300 BC to 650 AD

Teotihuacan rise and fall

+ Part 4: The Maya

Preclassic Maya existed since 2000 BC as primitive farmers, adopted chocolate somewhere along the way, and reached their height at 250 AD until their Collapse around 800 AD. We know Classic Maya elite revered chocolate, and were buried with vessels of it which were inscribed with hieroglyphs referring to cacao, images depicting humans and chocolate, and tested positive for traces of theobromine and caffeine. It’s unknown how the common Mayan took their chocolate, or if they were allowed to at all.

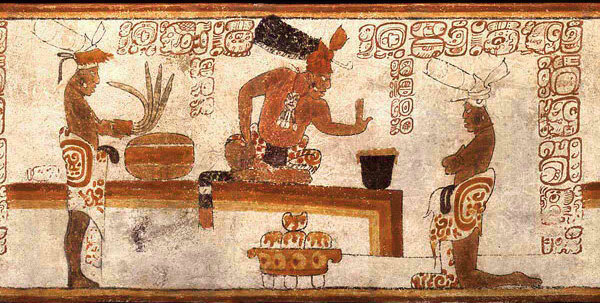

The earliest depiction of chocolate being made is seen on the Princeton vase of the Nakbè region in Guatemala. Chocolate was a drink, where cacao beans were crushed, and mixed with water and usually other ingredients. One important aspect of chocolate making was creating a foam on top of the drink (much like today we still prefer foam in the form of steamed milk or whip cream). Chocolate was poured from one vessel as high as one could hold it, into one vessel on the ground. This was done over and over until a great deal of foam built up. This foam was the prize of the chocolate drink for the Aztec, and likely for the Maya as well.

Classic Maya likely took their chocolate drink cold, hot, and in between, and incorporated other ingredients such as chilli. The Postclassic Maya were not only making chocolate drinks of varying temperatures, but also chocolate gruels, porridges, and possibly solids as well, while adding ingredients such as maize, sapote seeds, and vanilla.

Cacao became a driving factor in the Maya realm. Not only was it consumed as food, but cacao seeds were beginning to be used as currency. There is evidence from an Early Classic Mayan site in Balberta, Guatemala, of counterfeit clay cacao seeds. They were so convincing that experts in the 20th Century could even identify them as the criollo variety. Surely cacao was greatly valued by the Maya and was a driving force behind their commerce.

The Maya were also trading with the multicultural city of Teotihuacan, one of the greatest Mesoamerican cities before the Aztecs. Obsidian projectile points found in Balberta appear to be from Teotihuacan. It is likely that Teotihuacan received cacao in return, but no evidence of this exists. Currently there is no proof of the people of this great city consuming chocolate. However, they were a mix of Maya, Mixtec, and Zapotecs, and most likely consumed cacao.

After the Classic Maya Collapse, likely due to overpopulation and environmental degradation, the maya dispersed across the lowlands and highlands, while chocolate lived on.

Timeline

800 AD

Classic Maya Collapse

800 to 900 AD

Chontal Maya control many trade routes

950 to 1150 AD

Toltecs rise and fall

1150 to 1350 AD

Aztecs migrate South

1325 AD

Aztec capital founded

+ Part 5: Toltecs to Aztecs

After the Classic Maya Collapse in 800 AD, Mesoamerica entered into the Post Classic period. Some of the dispersed Maya became the Chontal Maya of Eastern Tabasco. They controlled many trade routes from Yucatan to as far as the Gulf of Honduras, with cacao being a major commodity. They have been referred to as the Phoenicians of the New World, being the middlemen of Mesoamerica. It’s believed the Chontal Maya invaded old Maya trading routes, and created a hybrid Maya-Mexican culture, of course carrying on the culture of chocolate making. By the 8th Century, they even established a mercantile kingdom on an old Teotihuacan trade route, where they stayed until they were defeated by the Toltecs.

The Toltecs existed from 950 to 1150 AD, and conquered lands already rooted in chocolate culture. They vanquished the Chontal Maya and took over the entire Yucatan Peninsula and their trade routes, fueling Toltec power. They were the next great presence since the fallen Teotihuacan, though not as imposing, before the Aztecs arrived.

The final great Mesoamerican power before the Spanish conquest were the Aztecs. They revered Toltec culture, received a great deal of their culture, while also linking their genealogy to them. They migrated to Central Mexico from an unknown region in the North as a Nahuatl ethnic group around 1150-1350 AD, after the fall of the Toltecs. Their roots are debated, and their stories contradicting. They founded Tenochtitlan in 1325, from which the Aztec empire grew. However, it’s likely people already existed in the Tenochtitlan area. The newly arrived Aztecs absorbed their cultures that contained elements of Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures (including chocolate). From those cultures, along with the Toltec, grew the next and final great Mesoamerican empire before the Spanish arrive.

The Aztecs took highly to chocolate, and conquered the finest cacao growing lands of Mesoamerica. Aztec culture was quite puritanical, with drunkenness being highly punishable, even by death. Because chocolate is non-alcoholic, it was therefore more favourable among them. Aztec warriors were even given wafers of solidified chocolate, so that they could mix it with water and turn it into “instant chocolate” during their campaigns. Cacao for the Aztecs was regarded as food, currency, and linked to divinity; it was treasured.

Timeline

1111

Aztecs migrate South into Central America

1325

Aztec capital founded

1427

Aztecs become greatest state in Mesoamerica

+ Part 6: People Of The Fifth Sun

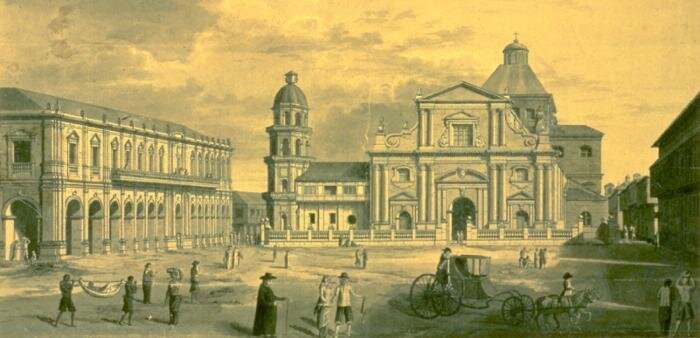

The origin of the Aztecs is debated. Their own historical records are intertwined with myth and folklore. They believe other worlds (or “Suns” as they called it) existed before our own, each one ending in catastrophe. According to them, we exist in the Fifth Sun, which was born in Teotihuacan (the great city before the Maya empire), and will also end one day. They migrated from a homeland they called Aztlan around 1111, until they established their capital, Tenochtitlan, in 1375. One hundred years later they had built their empire. Their capital, Tenochtitlan, had a population of 200 000, the largest city in the world at that time.

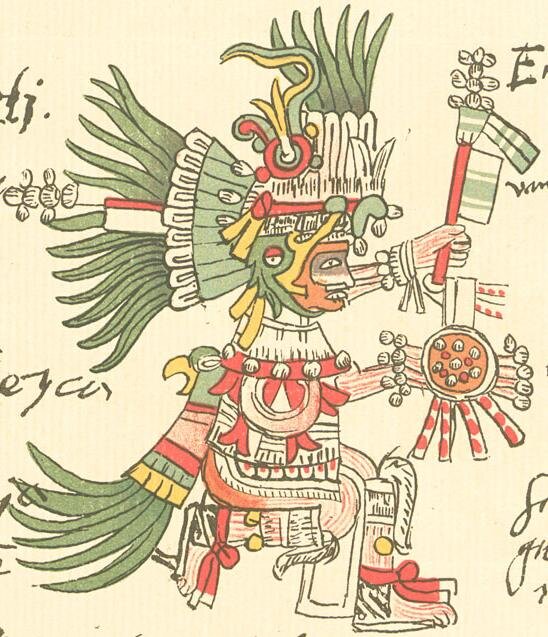

Huitzilopochtli was their state cult and ancient tribal deity. It was the supreme war god and the sun itself. This god required human sacrifice of captives of war so that the Sun would go on shining, otherwise the Fifth Sun would come to an end. Human sacrifice for the Aztecs didn’t have to do with an obsession with blood or death, but rather the fear brought upon by their beliefs that they would perish if they didn’t sacrifice. Cacao was associated with heart extractions during their once-a-year human sacrifices. The cacao pod came to represent the heart, since both could hold precious fluids, chocolate and blood.

One great conquest of theirs was that of Soconusco on the Pacific Coast of Southwestern Mexico. This area was coveted for thousands of years for its quality cacao trees. The Aztecs held an immense amount of cacao in storehouses that were heavily guarded, for cacao was not just food but currency as it was with the Maya. Of course, this currency had its counterfeits within the Aztec realm as it did with the Maya in the way of cocoa beans being shaped from wax, broken and carved avocado pits, or amaranth dough.

The Aztecs prepared their cacao as the Maya did, but they drank it cool rather than warm or hot. They added ingredients such as maize, silk-cotton tree seed, chili, ear flower, vanilla, and string flower (related to black pepper), creating many varieties of the chocolate drink. Chocolate was reserved for the elite, and the only commoners who could take it were soldiers.

There was even the belief recited through a tale that cacao was harmful to their health, making them heavy and age quickly. However, in spite of that they continued to drink chocolate, similar to how we today ignore health advisories against foods today that harm us.

Timeline

1502

Columbus encounters Maya traders on his last voyage

1519

Cortes encounters the Aztecs

1521

Collapse of the Aztec Empire

Ca. 1550 to 1570

"Chocolatl" enters Spanish vocabulary

+ Part 7: The Chocolate Conquest

Christopher Columbus encountered Mesoamerica during his final voyage in 1502, where he encountered Chontal-Maya speaking natives in trading canoes filled with goods, including cacao. Columbus’ son understood these cacao beans were very important to the natives, but Columbus never tasted chocolate as far as we know.

Hernán Cortés encounters the Aztecs in 1519, and defeated them two years later in 1521. The Spanish conquistadors encounter cacao, but appreciate it more for its value as a currency among the natives, and not so much for its taste. Cortés realized he could use the cacao to pay the wages of his native labourers. To offer an idea of the value of a cacao bean, a turkey hen was worth 100 cacao beans, 3 for an avocado, and 1 for a tomato. As for the taste of chocolate, It was a cool, unsweetened, watery, and a relatively bitter drink that the spanish found difficult to swallow. Natives would offer it to them, and to their astonishment, many Spaniards would refuse. Today, this would be similar to refusing expensive champagne.

The origin of the word “Chocolate” is debated, however it likely evolved from the word “Chocolatl” which is what the Spanish were calling it by the later half of the 16th Century. It’s believed that “Chocolatl” combines the Mayan word “Chocol” meaning “hot” with the Nahuatl word “Atl” meaning water. The Nahuatl speaking Aztec region is where most Spaniards lived, since it was where much of the gold was found. However, the Nahuatl word for chocolate is “Cacahuatl”. “Caca” in Spanish is the word for feces, and calling a thick brown drink “caca” may not work for them. Therefore, it’s hypothesized they replaced “caca” with the Mayan “Chocol” to get “Chocolatl”, eventually becoming “Chocolate”.

Eventually, a creolization occurred between the Spanish and the natives, with female Natives and male Spaniards. The females would take care of preparing the food, and continue their traditional chocolate drink. However, now to meet the taste of the new locals, chocolate has become sweetened, hot, and with old world spices added such as cinnamon, anise seed, and black pepper. As well, instead of pouring it from one vessel to another to create the foam, they used a wooden swizzle-stick called a molinillo.

Chocolate in Mesoamerica had now began to detach from its traditional ancient methods of preparation. Once it arrived in Europe, it would forever transform into something unrecognizable, and perhaps unpalatable, to the natives who first introduced it to them.

Timeline

1544

First recorded instance of chocolate in Europe

1585

First official shipment of cacao to Spain

Mid 17th Century

Chocolate becomes part of mainstream elite culture

16th to 19th Century

Method of preparing and taking chocolate goes relatively unchanged

+ Part 8: Chocolate Enters Spain

Chocolate left the creolized kitchen of New Spain and entered the Royal kitchens of the Spanish Court. Chocolate in Spain maintained its status as a drink for the elite (While by now it was available to all classes in the New World), but as medicine attending to the physical. It no longer was the divine sustenance revered by the Aztecs. It entered Renaissance Spain during a time where people had no concept of modern medicine, and cherished anything or any idea that may cure them of their ailments. For centuries many would swear by it while others cursed it, but the controversial seed would eventually be integrated into Spanish and European culture.

It’s not known when chocolate first arrived on the Iberian shore. No record exists of Columbus or Cortès having ever transported it on their ships back to Spain. The earliest we know of chocolate being brought to Spain, and Europe for that instance, is in 1544 by Dominican friars. The first official shipment of cacao beans was in 1585 to Seville, Spain, about 60 years since Cortès encountered it for the first time. A more likely scenario, though without official record, is that it was taken by the military, civilians, or clergy who visited the New World several times. Nevertheless, once it entered Europe it was there to stay.

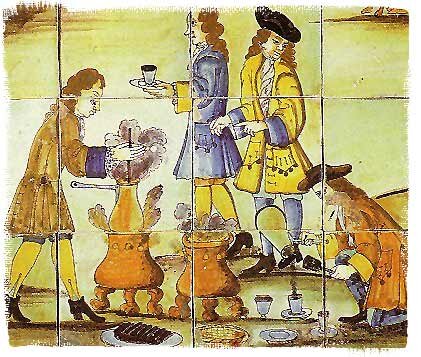

The Spanish prepared this creolized New World drink and served it stylized for the Spanish courts. They would roast the cacao, winnow it, and add powdered sugar, cinnamon, powdered vanilla pods, achiote, and sometimes musk. They would grind this into a paste and form solid cakes or bricks. When it was time for the chocolate to be served, they would add the cakes to hot water into a chocolate pot, and beat it with a molinillo to produce the froth. Just like the Mesoamericans, the Spanish would carry on the traditions of creating the froth on top of the chocolate drink. Today we still drink our hot chocolate with foamy formations, but usually from steamed milk or marshmallows. However, some countries such as Mexico and the Philippines still produce their frothy hot chocolate with a molinillo.

Although chocolate entered Spain during the Renaissance, it didn’t become widespread in Europe until the Baroque period. Even after arriving in Spain, it took about 100 years for it to be integrated into mainstream elite culture. Once this exotic drink became popular enough in Spain, it travelled into the rest of Western Europe. However, its preparation and method of taking chocolate wouldn’t change much for almost 300 years after entering Europe.

Timeline

1642

First recorded evidence of chocolate in France

1644

First recorded evidence of chocolate in Italy

1656

Chocolate reaches England

1670

First recorded evidence of Cacao in the Philippians

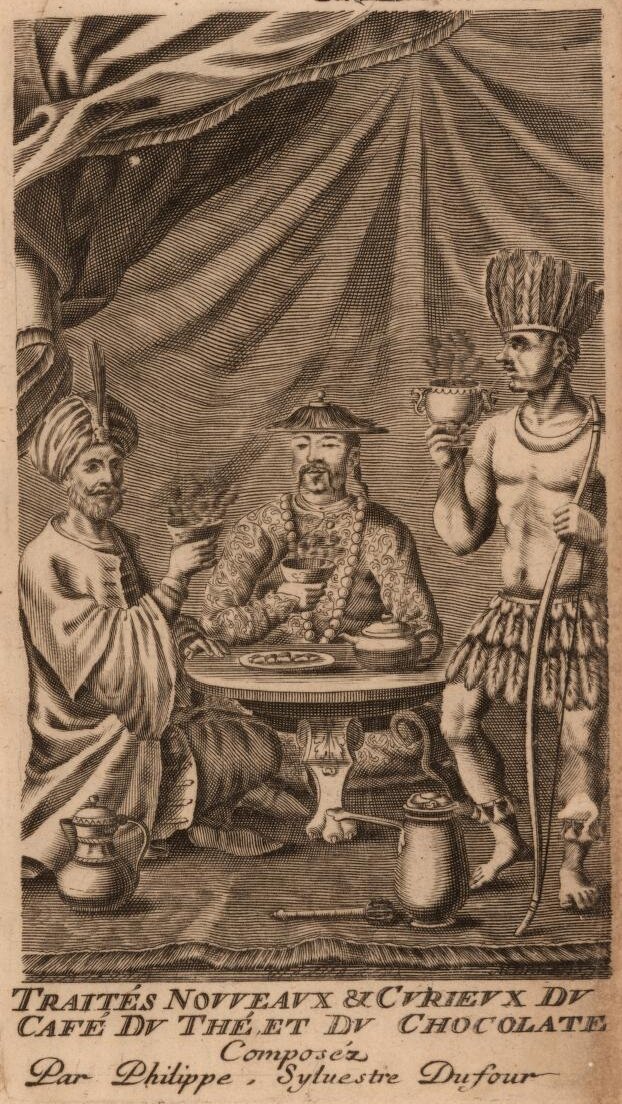

+ Part 9: Chocolate Enters Western Europe & Asia

Exactly how chocolate entered Europe is quite ambiguous and still debated. With all the movement between courts and monasteries throughout Europe, this “medicine” may have debuted itself in a more unofficial manner. Here are a few recorded instances of how the chocolate drink began to spread out from the Spain and the New World.

In France, the earliest evidence is in the 1642 documents of the Parisian physician, Rene Moreau, who was consulted by Alphonse de Richelieu on the properties of chocolate in order to help his spleen. Then, in 1659, Sieur David Chaillou was given exclusive rights to make and sell chocolate, signed by the king in 1666. A recipe for chocolate served in Versaille, a Tuscan recipe, included cacao, sugar, cinnamon, cloves, chilli, and vanilla. The French are also credited with the invention of the chocolatiere, a pot designed specifically for making and pouring chocolate. However, there is debate this pot may have originated in England.

In Italy, the earliest recorded evidence of chocolate is in 1644 by Roman physician Paolo Zacchia. He states chocolate is a drug, and was brought in from Portugal a few years earlier. It’s likely that chocolate then spread across Italy beginning in the Spanish owned Southern Italy through monasteries and convents that had ties to the New World and Spain. Jesuit priests had a large hand in the cacao trade, and likely were the ones who brought it into Europe. When chocolate reached Tuscany, they began adding additional flavours such as lemon peel, infused jasmine, and ambergris.

Chocolate reached England around 1656, however, they came into contact with it earlier while pirating Spanish ports in the New Spain. In 1655, England claimed Jamaica from the Spanish, including its cacao groves. In 1657, chocolate was being advertised in England as a cure for many diseases. Unlike Catholic Europe, England was now commercial and makers ran private shops, and didn’t have the time to prepare chocolate as they did in aristocratic France or Italy. They boiled the chocolate with water, eggs, and milk, while the cocoa butter collected at the top. A much more crude chocolate, which was even drunk from a bowl instead of a cup.

Cacao from Acapulco, Mexico was brought over to the Philippians in 1670 (or 1630 some sources say). The Philippines was the only Asian country for hundreds of years that would not only grow cacao, but prepare and consume chocolate. Soon after arriving in The Philippines, cacao arrived in Indonesia, however locals grew cacao trees but didn't take up chocolate culture as Filipinos did. Today, Filipinos still enjoy chocolate as a drink, using a tablet that gets beaten with milk and sometimes peanuts.

Timeline

16th Century

Grown in Guatemala, El Salvador; then Venezuela

17th Century

Martinique, St. Lucia, Trinidad, Brazil, Philippines, Indonesia

18th Century

Curacao, Ecuador, India, Sri Lanka; Forastero and Emelonado varities enter commerce

19th Century

Hawaii, Africa (Sao Tome, Principe, Bioko, Nigeria, Ghana), Cameroon

Late 19th Century

Singapore, Fiji, Samoa, Australia, Bombay, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Madagascar

+ Part 10: How Cacao Growing Spread Worldwide

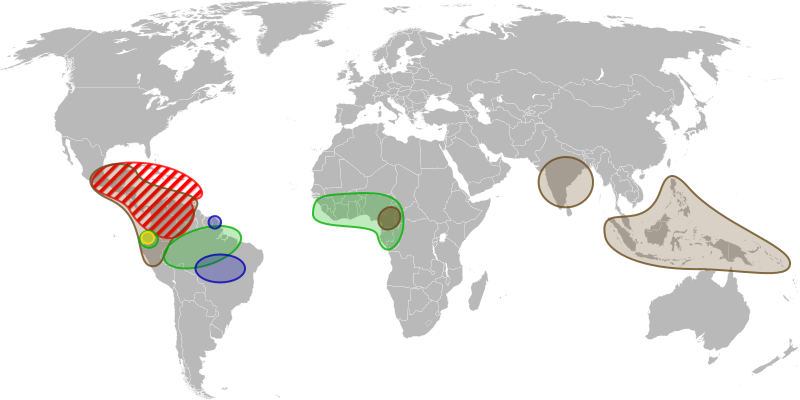

Commercial cacao growing began to spread across the globe in the early 16th Century, after Conquest, when El Salvador and Guatemala regions were producing the most cacao. Once Spain began to consume chocolate, demand for cacao rose, and cultivation then extended to Venezuela, being the first cacao grown outside of Central America for commercial use. As well, some sources state cacao entered Indonesia from Venezuela in 1560, but still debated.

In the 17th Century cacao then spread to Martinique and St. Lucia via the French in 1660, Trinidad via the British, Brazil via the Portuguese. Cacao was also brought from Mexico to the Philippines in 1670 (or 1630, disputed). From the Philippines, it spread to Sulawesi and Java in Indonesia (although some sources state it was Indonesia to receive it before the Philippines).

In the 18th Century, cacao was being grown on the Dutch owned island of Curacao. The Dutch also brought seeds from the Philippines to Jakarta and Sumatra, by 1778. During this time, cacao was also introduced to India from Indonesia, and then spread to Sri Lanka, with the earliest record being 1798 from Indonesia to Southern India. Up until now, criollo cacao was the variety being grown. In Ecuador and Brazil, another variety, forastero, was being cultivated during this time. Although not as aromatic and flavourful as criollo, it was robust, and above all, cheaper. Around the same time, the French brought the amelonado variety from the Amazon basin, to Bahia, Brazil in 1746.

During the 19th Century, cacao was introduced into Hawaii around the 1830’s. The newly cultivated forastero and amelonado varieties were then taken across the Atlantic by the Portuguese, from Brazil to Principe and Sao Tome in West Africa. From there that cacao made its way to the island of Bioko in 1854, Nigeria in 1874, and Ghana in 1879. It had been introduced into Ghana before by missionaries, but unsuccessfully. Germany brought trinitario cacao from the West Indies to Cameroon. Later on, other varieties of cacao would be introduced into West Africa. As well, Trinitario cacao would also make its way to Sri Lanka in 1834, 1835, and 1880, and mixed with varieties brought over earlier from Indonesia. The introduction into West Africa would prove to be successful, and today Ghana and Ivory Coast produce 70-75% of all the cacao in the world.

By the end of the 19th Century, Cacao travelled from Sri Lanka to Singapore and Fiji in 1880, Samoa in 1883, Australia in 1886, Bombay and Zanzibar in 1887, and Tanzania in 1893. Cacao was also sent from Sri Lanka to Madagascar during this time. Today, cacao is grown across the globe, anyway 20 degrees North and South of the Equator.

Timeline

1765

Chocolate industrialized in Massachusetts

1776

Hydraulic machine to grind cacao invented in France

1828

Coenraad Van Houten invents cacao powder

+ Part 11: Cocoa Powder Invented

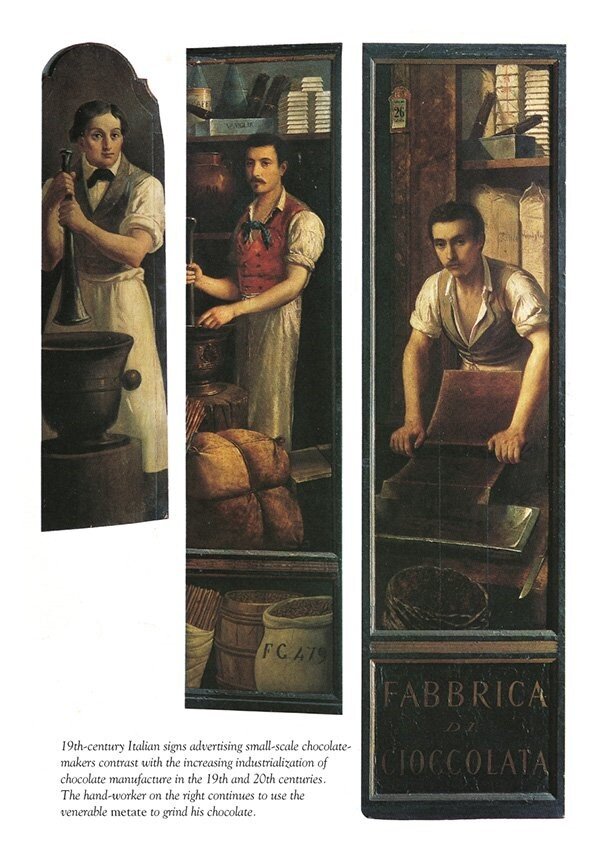

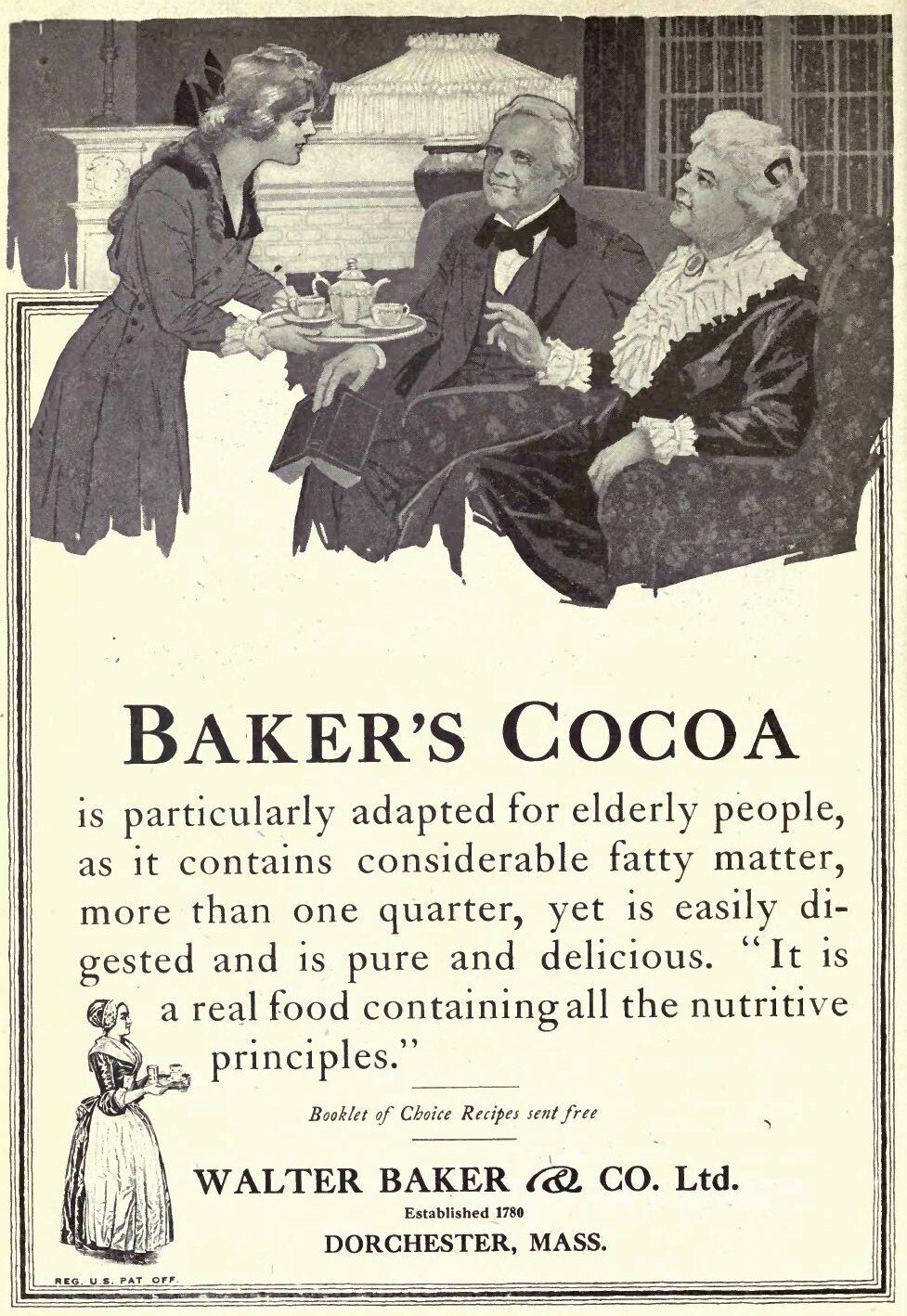

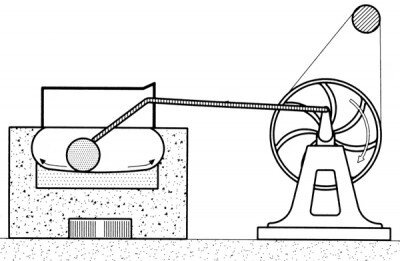

Up until the late 18th Century, chocolate was prepared by hand, but by 1765, Dr. James Baker and John Hannon of Massachusetts, USA, operated one of the first powered chocolate making machines. Their operation became the Baker Company, producing the well known Bakers Chocolate seen in North American stores today. In 1776, M. Doret of France invented a hydraulic machine to grind the cacao into a paste. This industrialization of cacao is one factor that allowed for the next revolution in chocolate, cocoa powder.

Cacao, like coffee and tea, was introduced into Europe during a time of exploration and colonization. The Dutch, like England, France, and Portugal, wanted in on this cacao commerce, and attempted to grow it where they colonized. The Dutch brought cacao over to Java and Sumatra in the 17th Century, and took over Curacao in 18th Century. Later in the 19th Century, The Dutch would play a significant role that would forever change chocolate.

European chocolate was prepared in ways similar and yet not so similar to how the Native Americans prepared it, such as pouring it over and over from vessel to vessel, mixed well, and and to be drunk right away. Europeans found trouble in the way cacao butter would separate in the mixture and float to the top, leaving an unpleasant and oily feeling in the mouth. Many would boil the chocolate until the fat came to the top, and skim the cacao butter out, however this proved very time consuming. In 1828 Coenraad Johannes Van Houten, A Dutch Chemist, invented cacao powder. His cacao press squeezed much of the cacao butter out of the seeds (from over 50% to 27% fat), created a hard solid “cake” of cacao, that would later be pulverized into a powder. This allowed the cacao to be more miscible in water, resulting in a more favorable drink. He also added alkaline to the cocoa powder which darkened it, mellowed the flavour, but most importantly enhanced miscibility even more. This is how most cocoa powder is made today, and the reason it’s coined “Dutched”.

The industrialization of chocolate making brought the price of chocolate down, and the invention of cocoa powder made it easier to use. Chocolate in Europe was becoming more available to a wider range of classes, and as the monarchies lost their exclusive grip on chocolate, the common man could begin to enjoy this exotic drink as long as he had the means to pay for it.

Timeline

1847

Fry & Sons invent the first eating chocolate

1868

Cadbury intorduces first box of chocolates

1879

Nestle Peter invent first milk chocolate; Lindt introduces the longitudinal conche

1894

The Hershey Company is founded

+ Part 12: The Chocolate Bar

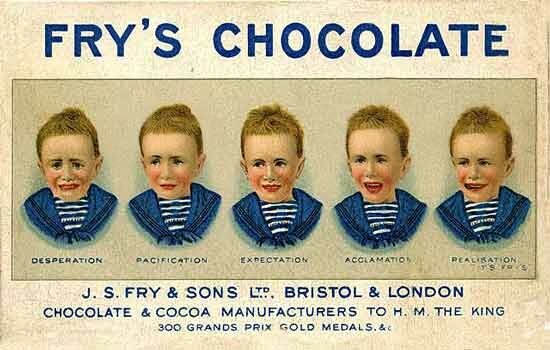

With the invention of cocoa powder, cocoa butter had become a byproduct that no one had much use for, was available to anyone who would take it. Back in the 16th C they would use cocoa butter to heal wounds, today we use it in the cosmetic industry for younger skin. Fry & Sons are a chocolate maker who established themselves in Bristol, England in 1728. Industrialization allowed for cheaper chocolate and very cheap cocoa butter. In 1847, Fry & Sons combined the cocoa powder, cocoa butter, and sugar to create the first chocolate bar.

They called it “Chocolat Delicieux a Manger” or “eating chocolate”, marketed with a French cachet. However, eating chocolate wasn’t exactly new. Pre-Colonial Mesoamericans were making gruels and other foods with chocolate. Europeans in the 18th Century created chocolate pastilles, desserts, pasta, and main dishes with it. However, unlike the pastilles that were very brittle and tasted dry, Fry’s chocolate was considered smooth, and melted in your mouth due to the extra cocoa butter and fine particle size of the cocoa powder. It was the first time we know of that chocolate was made to be eaten as a solid. It was the first solid chocolate version of the 5000 year old drinking chocolate.

They exhibited this eating chocolate in Birmingham, England, in 1849, where John Cadbury operated a coffee and tea shop since 1822. In 1866, George Cadbury (John’s son) obtained a model of Van Houten’s machine and began to create his own cocoa powder. His brother, Richard Cadbury, introduced the first “box of chocolates” in 1868.

Francois Louis Cailler opened the first chocolate factory in Switzerland in 1819, making chocolate more available to the Swiss market. In 1867, a Swiss chemist, Henri Nestle, invented powdered milk. He combined forces with Daniel Peter, another Swiss chocolate manufacturer, and in 1879 they invented the first milk chocolate bar. In the same year, Rudolf Lindt, another Swiss chocolate manufacturer, invented the Conche. Up until now, chocolate was a bit gritty, but conching allowed the particles to be ground smooth enough that particles couldn’t be detected in the mouth. The process also mellowed out the intensity of chocolate by allowing the harsher aromas to evaporate out. So in 1879, the Swiss created the first milk chocolate bar and the smoothest, forever making their mark in the chocolate industry.

In 1894, the Hershey Company was founded in Pennsylvania, where chocolate was manufactured on an enormous scale, and became a major competitor and billion dollar company. It led the way for the inexpensive, sugary, candy bar industry of the 20th Century.

Timeline

16th to 17th Centuries

Chocolate adulterated with grain flours, animal fats, and brick dust to name a few

20th Century

Chocolate adulterated with high levels of sugar, synthetic fats, and artificial flavours

21st Century

Growth of small scale artisan and bean to bar makers

+ Part 13: 21st Century Chocolate

By the late 20th Century, chocolate had been transformed into something that would be unrecognizable to the Mayo-Chinchipe who were consuming chocolate about 5000 years earlier. The Mesoamerican chocolate was a dark, bitter, watery, and often spiced cool drink, and has now become a high fat, highly sweetened confection often associated with being unhealthy. It’s no longer the expensive and exotic treat of the aristocracy, or a medicine prescribed by physicians of the 17th and 18th Century. It’s become so cheap that it’s one of the most affordable foods in grocery stores today.

Industrialization and post modern consumerism transformed chocolate into what it is today. Mass production, high sugar content, and adulterating chocolate are a few factors that have contributed to bringing the cost low enough that chocolate bars can be sold for less than $1 and still be profitable for those manufacturing them.

Adulturinag chocolate has existed since the 16th and 17th Century, when manufacturers in Europe would add grain flours, lard, egg, and even brick dust. Today these adulterations comes in the form of high sugar content (which is an extremely cheap ingredient), artificial flavours, and synthesized cocoa butter replacers (CBR), and other vegetable fats. CBR’s are synthetically produced fats, that benefit the manufacturer because they are a cheaper fat than cocoa butter. Vegetable fats such as palm oil often leave an unpleasant, sometimes waxy feeling in the mouth. As well, over 70% of the world’s cacao grown is considered a lower quality, grown solely for profit and not for flavour. Most cacao growers (especially in Western Africa) make less than $1 a kilogram for their cocoa beans, and often turn to other more profitable crops such as soy or coconut.

While many have become accustomed to chocolate with high sugar content and other adulterations, many have pushed for stronger regulations on chocolate manufacturing. In the late 20th Century, France and Belgium pushed for stronger regulations in Europe, and other countries soon followed. Makers like Bonnat in France added a premium to their chocolate for those who were willing to spend more on better tasting and better quality chocolate.

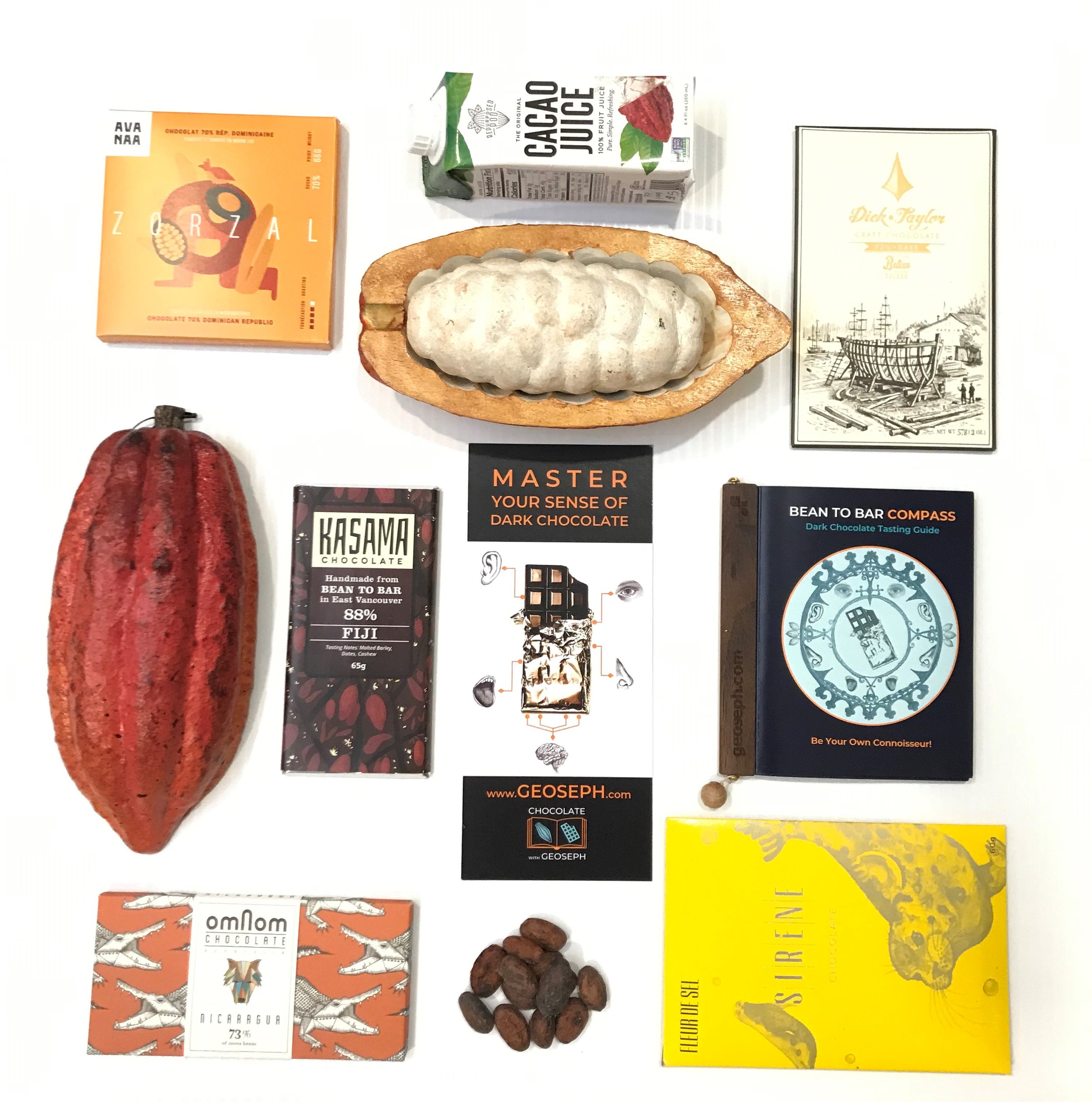

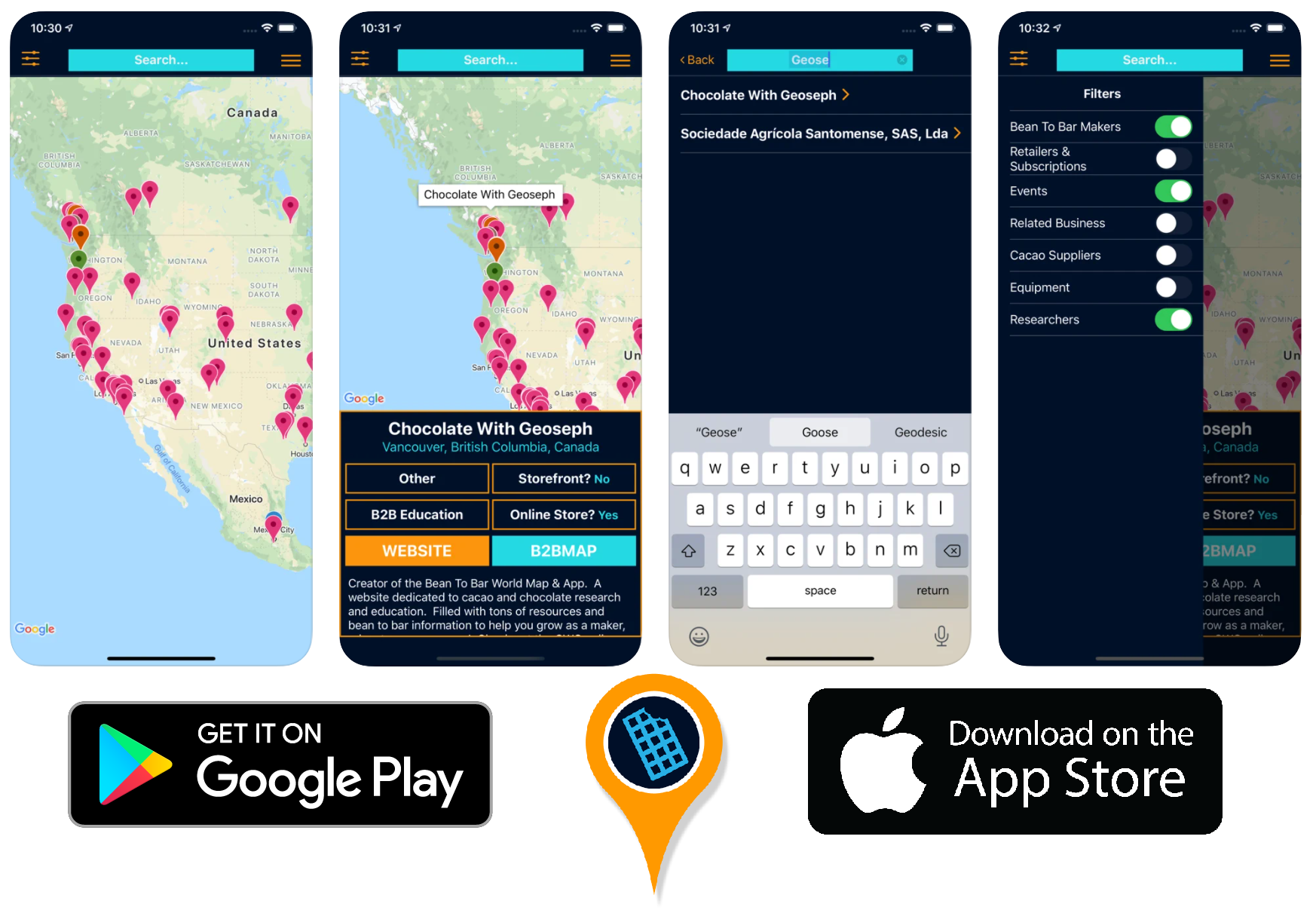

This gave way to the explosion of artisan chocolate melters and Bean to Bar makers of the 21st Century. Just as chocolate was ground by hand in Mesoamerica and 15th-18th Century Europe, today artisan makers are using machines that allow them to make high quality chocolate in small batches. These chocolates are more expensive, mostly due to better quality cacao (which costs more to produce, often paying growers $8 and up per kilogram), higher quality ingredients, no or little adulteration, and small scale manufacturing.

It can be overwhelming to know which chocolates are worth the extra cost. Which manufacturers are being fair to their growers, and maintaining the flavour integrity of their chocolate. The best way is to educate yourself, ask questions, and then let your taste buds decide.