Part 1

Part 2

Part 3: Chocolate Process

Chocolate Makers & The Process

What role do the chocolate makers play in regards to flavour? This page will be updated as new information is received. Last edited January 3, 2019.

The chocolate makers, who take the cacao and transform it into chocolate, have a profound impact on the final flavour of the chocolate. Think of chocolate makers as composers of flavour, where they apply their skills and craftsmanship to form a symphony of flavour within each batch of chocolate. These aspects include but are not limited to:

Sorting

Roasting

Winnowing

Grinding

Conching

Aging

Tempering

+ Sorting & Cleaning

Once the chocolate maker receives the cocoa beans from the growers or third party brokers, they need to be sorted and cleaned. Because the cacao beans are often laid out in the open to dry, they are exposed to environmental elements, debris, and animals.

Debris such as nails, rocks, feathers, as well as mouldy or deformed seeds, and coffee beans can end up in a sac of cocoa beans. These need to be removed by hand before proceeding. This debris can make the chocolate unsafe to eat, harm the equipment, or impose off flavours into the chocolate.

Raw Chocolate

This is often a concern for many when it comes to raw chocolate. Raw chocolate is made from cacao seeds that are not heated at a high enough temperature to kill off potential harmful organisms or elements that may make us ill. When a maker is sorting through his seeds, it becomes apparent how important it is to roast them for health concerns. However, the small sector of raw chocolate is only growing, and many appear to be not be negatively impacted by consuming it.

+ Roasting Forms Flavour

This is when the seeds begin to smell and taste like chocolate!

The cocoa beans are roasted somewhere in the region of 15-20 minutes, depending on the characteristics of the seeds. The amino acids and reducing sugars created during fermentation, marry together over the heat to form hundreds of aroma compounds. Pyrazines, a group of aroma molecules, are formed here, and are the most important and most numerous aromas found in chocolate.

Roasting also dries out the seed further to less than 2% moisture content, which is important to the texture of the chocolate as well as its viscosity. Too much moisture will cause the liquid chocolate to become very thick and difficult to manage.

Makers who use lower quality beans, which are often more bitter or contain off flavours, will also often over roast their beans to mask or cook off the off flavours of their beans.

During roasting, reactions take place, including the Maillard Reaction, Strecker Reaction, and caramelization. At temperatures between 120-140*C, most microorganisms (yet not mycotoxins) are killed.

Temperature

Roasting the beans at high temperatures remove the bitter volatile acids, such as ethanoic acid. Less volatile acids, such as ethanedioic (oxalic) and lactic acids are unchanged by roasting.

As well, the formation of pyrazines (volatile aroma molecules) and their quantity depends on the temperature and duration of roasting.

Maillard Reaction

The Maillard Reaction is a "flavour machine" reaction. Hundreds of reactions occur, which result in a browning colour (such as in grilled meats or baked bread) and a complex array of new aroma molecules (particularly baked, toasted, and roasted) that were not there before the reaction. Simply put, it's the marriage of amino acids and reducing sugars (glucose) via heat in the presence of water. Remember fermentation? These amino acids and reducing sugars were created when proteins and carbohydrates were broken down at this stage. Now they are being used to develop new aroma molecules!

These reducing sugars and amino acids form what are called Amadori compounds. These amadori compounds then go on to help form 3-deoxyhexulose and 2,3-enediol. From these, a-dicarbonyl compounds are formed, which then go through what is known as the Strecker Reaction.

Strecker Reaction

Roasting also involves the Strecker Synthesis, which forms aldehydes, ketones, pyrazines, pyrroles, and pyridines (aroma molecules) from amino acids (formed during fermentation) and 2-oxopropanal. These reactions also involve the formation of group of aroma molecules found in chocolate. These reactions also induce the production of melanoidins, giving cacao their brown colouring.

The characteristic smell of chocolate can also be produced by the reaction of amino acids such as leucine, threonine and glutamine with glucose, when heated to about 100*C. Higher temperatures will produce a much more penetrating/pungent smell.

Polyphenols

Polyphenols are molecules often associated with antioxidant activity. There is the debate that processing cacao (fermenting, roasting) eliminates many of these favorable antioxidants. This is the main case for "raw" chocolate movement. However, although this is true, the process also begins to form new polyphenols, and longer chained ones, that may even have a prolonged affect in our bodies since they take longer to break down. Antioxidants in chocolate have been shown to aid against cardiovascular disease, decrease inflammation, and even improve cognition and/or memory. The types of polyphenols present also affect the bitterness of cacao seeds, and in turn the final flavour of the chocolate.

+ Winnowing to release flavour

Winnowing

Winnowing is an ancient method of removing the husks or casings from around the kernel of seeds and grains. The roasted cacao seeds become fragile due to their very low water content. The roasting causes the moisture within the seed to turn into steam which forces the testa (outside casing of the seed) away from the inner kernel. When the roasted seeds are crushed, the testa easily falls off the kernel (or "cocoa nib") and the two parts are mixed together.

Air is then blown over the mixture. Sometimes the mixture is allowed to fall in a chamber while a vacuum sucks the paper light outer casing while the heavier nibs fall into a chamber, separating them both.

The husks are a waste product, but today are being used for many purposes such as garden mulch, to infuse into beer (the husks contain the cocoa flavour as well) or even to make a tisane (steeping the husks in hot water). Some people have issue using husks as a tea or other edible purposes since they were exposed to the elements, including the bacteria, moulds, and yeasts during fermentation. Roasting appears to kill off any unfavorable elements, but spores and microscopic creatures may persist even afterwards. Take caution if ingesting husks in some way.

The separated cocoa nibs go on to make chocolate. The removal process of the husks also releases acidic molecules held within the husk, allowing some of the acidity to escape.

+ Milling & Melangers

Cacao used to be ground by hand using a metate usually placed over a small burning flame to warm up and melt the cacao nibs.

Today, machines are used to grind up the cocoa nibs (kernels of the cacao seed) into a paste, first on their own, then with sugar (and powdered milk if milk chocolate is being made).

There are a variety of machines to grind chocolate. They grind up the cacao nibs and turn them into a thick paste. After which, the chocolate is sent to a conche to fine tune the flavour.

Many craft chocolate makers today are small scale and use a melanger to mill and fine tune their chocolate all in one machine. They are often composed of a basin with two rolling stone mills. This is more cost effective than using a miller and conche, but they have less control over the balance of texture and flavour in their chocolate.

The other option is to use a mill to grind the cacao and sugar particles to under 30 microns, until our mouth can't detect the particles. Many makers use roll refiners, that pass the chocolate through rollers that move at varying speeds.

The grinding process breaks apart the cell walls of the kernel (cocoa nib), and the heat from grinding begins to warm up the cocoa butter until it liquifies. As this occurs, volatile aromas are being evaporated into the air, specifically the more astringent compounds and acids.

Rudolf Lindt

+ Fine tuning in the Swiss Method

A conche is a machine that further develops the flavour of the chocolate. It allows the harsh volatile aromas, especially the acidic ones, to evaporate, leaving behind the more favorable aromas such as cherry, plum, or toast, for example.

This revolutionary machine was invented in 1879 by chocolate maker Rudolf Lindt of Switzerland. His chocolate company was later acquired by another chocolate maker, Chocolat Sprüngli AG, in 1899.

In the 19th Century, mills didn't grind the eating chocolate as smooth as the chocolate we know today, and so his machine did just that. His chocolate was known as the smoothest, silkiest chocolate around. Today, many mills can effectively grind the particles, but the conche also has another function.

The heat and motion involved allows for the astringent and acidic aromas still contained in the chocolate to evaporate out, leaving behind the more favorable aromas a chocolate maker and consumer desires. However, conching too long will allow for many of the aromas to escape, favorable and unfavorable, leaving behind a more one-dimensional tasting chocolate. This is one reason why chocolate you purchase in the supermarket, although tasty, is one-dimensional as far as flavour. It simply tates like chocolate, while artisan and craft chocolate contain varying aromas within the matrix of the chocolate flavour.

Bulk chocolate

However, over conching will turn the chocolate quite bland, as not only will the harsh aromas evaporate, but the favorable ones as well. This is a concept some makers who use "bulk" cacao (cacao that is more bitter and less flavourful) use to remove the off flavours from the cocoa beans and the over roasting. This is one reason why chocolate sold in supermarkets carry one flavour, cocoa. They often conche it longer to make up for the fact that they used bitter over roasted cocoa beans. Chocolate made by craft and artisan makers is often more vibrant, tasting like chocolate yet with additional notes such as cherry, plum, and toast. All these aromas come from the cocoa bean itself and how it was processed, they are not added into the chocolate.

This is one major aspect that separates fine chocolate from bulk commercial chocolate. Fine chocolate contains a complex arrangement of aromas that was achieved by using quality beans and properly processing them. Commercial chocolate still tastes great to most people, especially since most of it has higher amounts of sugar and or milk added, but it doesn't have the same complexity in flavour as fine chocolate.

After the chocolate flavour is developed to the makers preference, it is emptied into vessels. Often, but not always, the chocolate is allowed to age.

+ Age

After the conche or melanger, the chocolate is poured into blocks and allowed to rest for a few months or so, according to the makers preference.

As the chocolate rests, the flavours mellow out and allow for the chocolate to reach its desired flavour profile.

+ Beta V: The polymorph of choice

Tempering in a nutshell

Cocoa butter, the fat component of chocolate, crystallizes into 6 different polymorphs. The ideal polymorph for the chocolate bar is Beta V.

What's a polymorph? In chemistry, it specifies a substance (cocoa butter in this case) that can crystallize into many forms ("Poly" meaning many, and "morph" meaning form). Just as carbon has many polymorphs (diamonds and graphite being two examples, so does cocoa butter. Chocolate (or the fat to be specific) can take on different properties as it solidifies, depending on which of the 6 crystal forms takes prominence. Just as carbon can form into a beautiful shiny clear diamond, or a grey chalky graphite, chocolate can form into a beautiful shiny dark mono-tone desirable form, or a mottled whitish and chalky undesirable form.

What does this have to do with flavour? Texture, melt, and flavour release.

If tempered properly (Beta 5 crystallization) the chocolate will take on the form of a shiny, one-toned brown surface, will snap when you break it, and will melt just below body temperature. Other forms can be mottled, whitish, crumbly, with varying melting points; not ideal.

The way the chocolate liquefies in our mouth, and the textures involved, affect our perception of its flavour. If the chocolate is made well, it will have a smooth creamy melt. Off-tempered chocolate (not in the beta V polymorph) will feel more chalky, and take longer to release its flavour, which may also appear more dull.

Tempering Specifics

Chocolate is generally tempered by warming it to above 45 degrees Celsius to melt out all the cocoa butter crystals. The crystals form at varying temperatures, but above 45 they all break down.

Properly tempering chocolate requires you to cool down the 45 degree chocolate very quickly to, in the case of dark chocolate, around 29-30 degrees Celcius. However, motion is also an important aspect of tempering. Cooling it down quickly combined with stirring and motion will ensure a good temper. This can be achieved by adding seed (already tempered chocolate or cocoa butter with plentiful beta V crystals) into the warm chocolate, or by shoking the liquid chocolate by pouring it onto marble or granite, which will encourage the growth of beta V crystals.

Once it reaches that temperature, enough of the beta V crystals exist within the chocolate that it will properly crystalize when it cools. It is often heated up again a couple of degrees so that the chocolate doesn't crystalize too quickly.

How to know it's tempered?

A quality temper is one that allows for the chocolate to produce a surface that is smooth, shiny, and a single shade of brown. It will snap when broken, and melt just below body temperature. It's also at its optimal state for tasting!

Chocolate that is not tempered properly or has gone out of temper due to heat from improper storage, will lead to a whitish, mottled and less vibrant chocolate bar. It is still edible, but will not have the same melting or even tasting properties when eaten as a solid. For tasting purposes, this can be fixed by melting it and enjoying it as a liquid!

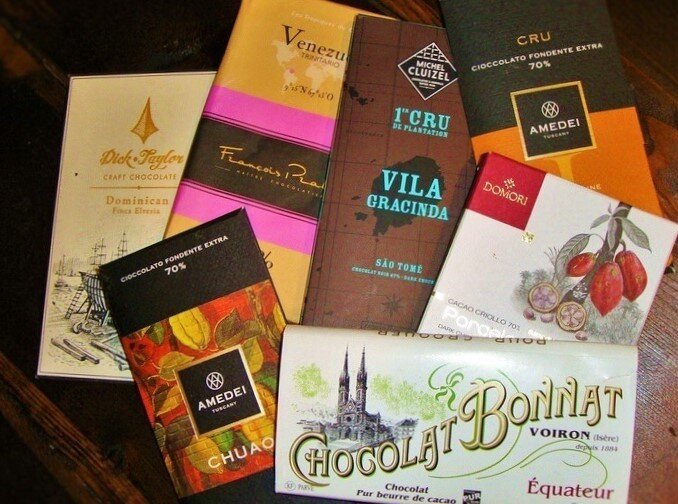

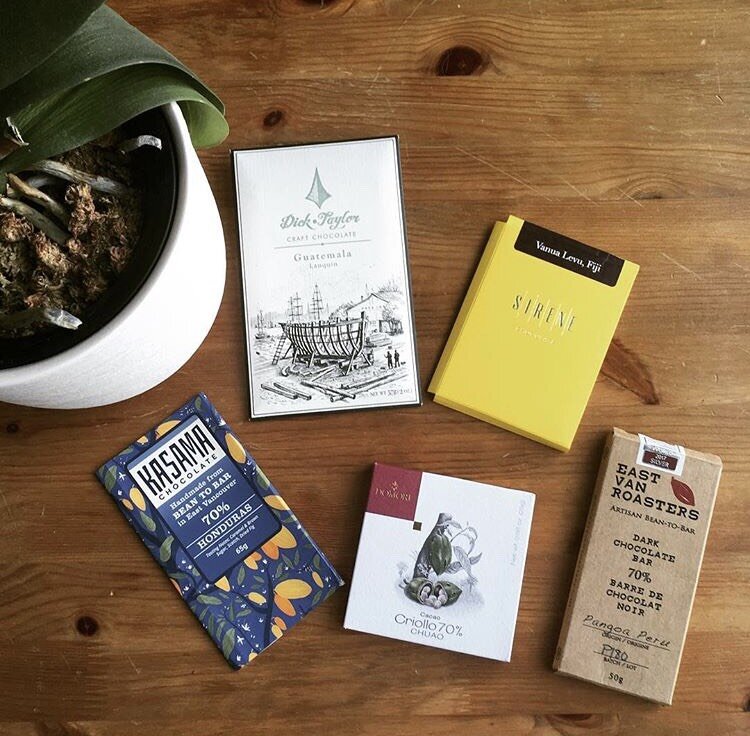

+ Chocolate Bar

The pride and joy of any chocolate maker. You can get an idea now of the amount of work that goes into making a chocolate bar. It's much more involved than grinding up some cacao beans with sugar and expecting it to taste delicious.

Remember, these cacao beans are grown in countries far from where they end up. Once they arrive to the manufacturing facility, they go through many steps in order to become chocolate. This is a highly processed food. Not in the negative way "highly processed" is used today in regards to nutrition, but highly processed as a tertiary food product. There are many steps involved, and it requires lots of time and manpower.

Some may be put off by the cost of fine and craft chocolate in the market today, costing anywhere from $6 - $14 a bar. However, if you think of the amount of manual labour that goes into making them, it's more amazing that other makers can sell their chocolate for $1-$3 a bar and still make a hefty profit.

That said, a high costing bar doesn't distinguish it as high quality or tasty, but you do often get what you are paying for. The better you understand quality, the better you'll be at discerning it. Learning how to "taste" chocolate is the first step in understanding the flavour of chocolate, and then you'll be equipped to be a better judge of quality.

Aroma Library

Check out an aroma library I have been creating. It’s a list of aroma molecules found in cacao and chocolate at various stages. It offers you an idea of where the flavours in your chocolate are coming from. It’s a growing list, so check back often.